House of Memories

Formerly: Burmese Independence Army Headquarters

Address: 290 U Wizara Road

Year built: Unknown

Architect: Unknown

This villa-turned-restaurant displays unusual features for a colonial residence. It is more akin to British homes in the hill station of Pyin Oo Lwin (then Maymyo), in Shan State, where colonial officers grew strawberries and escaped during their holidays in search of cooler weather.

As you turn off U Wizara Road and into the driveway, the heat, fumes and heaving traffic subside, giving way to a gentler aura: when the authors of this book arrived for an afternoon drink, staff were enjoying a leisurely game of five-a-side football in the courtyard at the front.

The house displays many of its original features, save for the makeshift roofing which suggests repairs prompted by weather damage.

The house was at one time known as the “Nath Villa” (a sign at the front gate still bears that name) and belonged to Mr Dina Nath—Chairman of the Indian Independence Army’s chapter in Burma—and his wife, Caroline. The Nath family still owns the house and as their grandson, Richie, explains: “I thought about renting it out, but I couldn’t do it.” Instead, they converted the spacious house into a pleasant restaurant which, as the name suggests, doubles up as a homage to the Nath family and their heirlooms. A number of private dining rooms are named after Nath family members, save for one on the first floor which features a grander name still: it was the office of none other than General Aung San.

Indeed, and like in a number of other properties around town, General Aung San struck up quarters here for a time. The Naths, also active in the anti-colonial struggle, gave Aung San a room in 1941. Dina Nath also brokered meetings between the Indian Independence Army and Aung San. The IIA’s leader, Subhas Chandra Bose (who, like Aung San, colluded with the Japanese at the start of the war) stayed here during clandestine visits to meet with Burma’s independence leader.

As the Nath family recount on the restaurant website, Dina Nath was subsequently imprisoned for a year by the British, in 1947, for his role with the IIA. Rajiv Gandhi, prime minister of India (1984–1989), later honoured Nath’s role in the independence struggle. The house features many photos of Nath’s momentous life.

The house is well preserved but clearly delicate. The staff politely ask you not to run or jump on the first floor’s teak floorboards. (And as the authors were writing this text on the first floor’s airy terrace, a small piece of the roof came crashing to the ground.)

Drugs Elimination Museum

Address: Kyun Taw Road

Year built: 2001

Architect: Unknown

In a city full of surprises, this may be one of Yangon’s more surreal buildings. First there’s the premise: an entire permanent exhibition dedicated to class-A drugs and Myanmar’s (frankly dubious) triumphs in stopping their production. And then there’s the building itself: impossibly vast and imposing, with vague allusions to pagoda architecture, especially the tiered roof design and the canopy—although bizarrely, this one is held up by Roman Doric columns. The overgrown and empty surroundings, colonised by stray dogs, are rather haunting.

The façade is tiled a creamy beige. The logo of the Central Committee for Drug Abuse Control—a hand setting fire to opium poppies—adorns the alternate spaces between the three storeys’ mirrored windows. The logo also appears on the entrance’s heavy wooden doors.

But nothing prepares the visitor for what they find inside: first a deathly silence, ominous enough to discomfort even the most hardened drug users. (Presumably.)

The entrance features a vast portrait of Myanmar’s erstwhile leader, Than Shwe, surrounded by adoring officials. By the picture he is quoted announcing that his government would do its “utmost with whatever resources and capability we have in our hands to fight this drug menace threatening the entire humanity”.

Throughout the museum’s never-ending floors, visitors are treated with detailed descriptions of the global drug trade and the basics of industrial drug production. Fake ecstasy pills are pinned to the wall and itemised, like rare butterflies. You will also find photos of apprehended producers and traffickers and victims in the advanced stages of addiction. Haunting paintings adorn the walls, illustrating the medical and figurative torments of drug abuse along with captions like “From insanity to death”.

After the bloodbath of 1988, the junta reeled from international condemnation and sought ways to boost its international profile. In an article about the museum, Vice, an American magazine (with a loud, proud and liberal take on recreational drug consumption) notes that there were “650 square miles of opium-producing fields scattered throughout Myanmar, and 80 per cent of New York City’s street heroin arrived by way of Southeast Asia’s notorious Golden Triangle” in the 1990s; the bizarre museum showed a government “desperate for good PR”, in Vice’s words.

Today the problem is far from eradicated. Myanmar is the largest producer of methamphetamine and a mixture called yaba (methamphetamine and caffeine) is ravaging the country’s youth in many impoverished areas. While Myanmar’s war on drugs did appear to make some headway until the mid-2000s, poor farmers are returning to heroin production for lack of other options. Poppy cultivation nearly tripled between 2006 and early 2015.

University of Medicine-1

Formerly: Rangoon College of Engineering

Address: Pyay Road

Year built: 1954-1956

Architect: Raglan Squire

The architectural profession in post-independence Myanmar began with the introduction of a degree programme at Rangoon University in 1954. It took another four years for the first five students to graduate. U Tun Than, who designed the Children’s Hospital in Dagon township, was in that first small cohort. Back then, all the students knew Raglan Squire.

Squire was born in London in 1912 and read architecture at Cambridge in the interwar years. He founded his first practice in 1937, but would soon serve with the Royal Engineers during the war. He was an influential member of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) Reconstruction Committee during the rebuilding of London after the war. His conversions of townhouses into apartments on Eaton Square, in Belgravia, are especially notable.

Squire was chosen to build the new Engineering College of Rangoon University. This was evidence of the government’s desires to attract a forward-looking, international architect to post-independence Yangon. Squire first came to Rangoon in November 1953. For the Brit, the “contrast to fog-bound, cold London, was too much”. He was taken on a night time drive through the streets of Yangon and, in his autobiography, writes that he fell in love with Burma and the Burmese that night. His plans for the complex delighted the government, who pushed him to start building as soon as possible—Prime Minister U Nu came to lay the foundation stone. Squire brought a large team of experienced architects and engineers from the UK. The total payroll exceeded 100 people, although it was bloated by extensive domestic staff employed by the expats.

Just like Squire’s Technical High School, this was a comparatively expensive building for impoverished post-independence Burma. Funds were made available via the Colombo Plan and were therefore indirectly provided by the Americans. For those countries in the region that had strong domestic communist movements, accepting aid outright from the United States was politically contentious. It was also the aspiration of many newly independent nations in Southeast Asia to be perceived as non-aligned. Therefore, accepting funds and technical assistance from a multilateral mechanism like the Colombo Plan was an expedient loophole.

As you approach the complex, the main library building sits perpendicular to the street and is visible from far down Pyay Road. Note the canopy covering the entrance area. A large rectangular window on the street-facing side appears like the only opening of the tall building’s façade. Raglan Squire said of the Library building, the tallest in Yangon at the time:

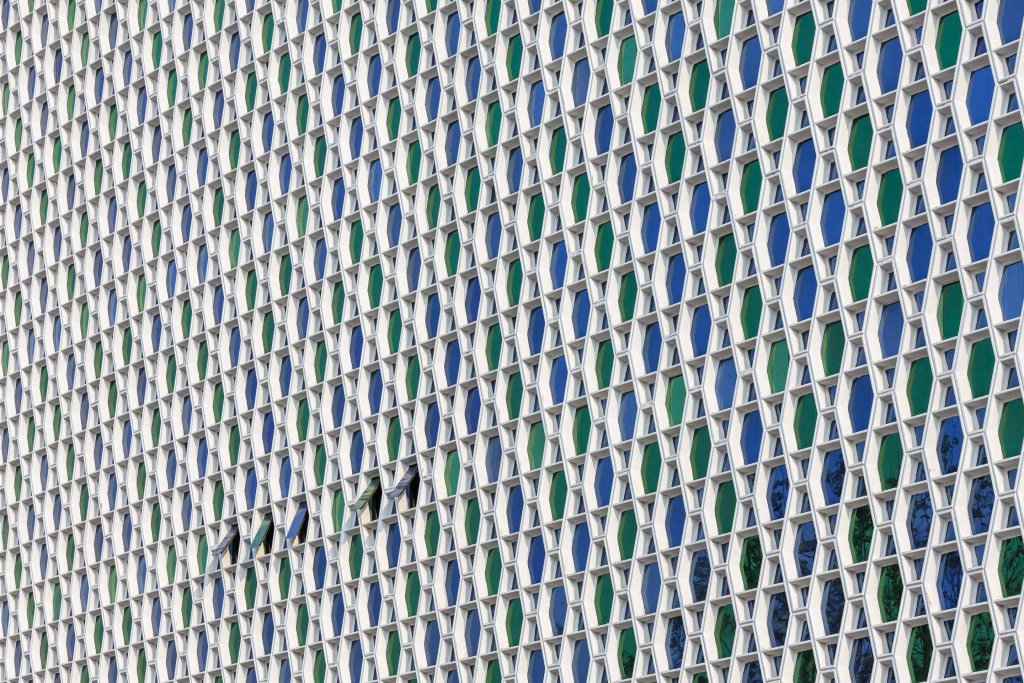

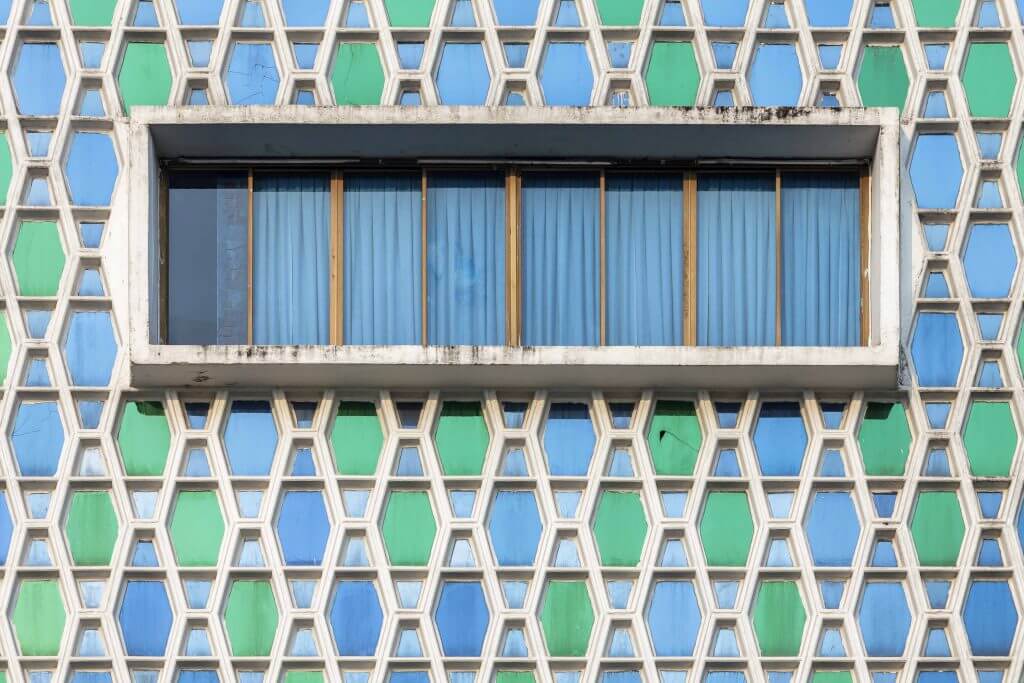

“The Library building would be multi-storey and, therefore, presented different problems. I finally decided that I would clad the whole of this building with precast, coffin shaped, panels; into these panels I would fit different coloured glass strips assembled in the form of louvres. The result would be a building that would be gently ventilated, through the louvres, along its total length and which would receive, through the different coloured glass, a kind of dappled daylight effect like the lightning in a tropical jungle.”

The rest of the complex consists of lower building wings containing more lecture theatres and classrooms. In a time before air conditioning, the overarching design inspiration was the extreme climate (a recurring feature in this book, as you may have noticed).

Squire personally commissioned Burmese artists to design various murals and bas-reliefs in the courtyard; these have been very well preserved. Just like the ones installed at the Technical High School, they portray idyllic and optimistic displays of traditional life in a (newly) independent Burma. It is worth exploring the entire compound, which at 60 years of age exudes the same forward-looking modernity of its younger days.

Raglan Squire regarded this commission as the high point of his career (which continued until his retirement in 1981). What earned him the most attention internationally were not the concrete buildings, but a structure that has since disappeared. Indeed, Squire also designed a wooden assembly hall, which locals quickly dubbed “Laik Khone” (“back of the tortoise”) due to its peculiar shape. It was a remarkable piece of timber engineering, its stability testimony to the quality and resilience of Burmese teak. In some places of the concave assembly hall’s structure, eight layers of wood were stacked on top of each other, made possible by advances in timber design techniques. Better adhesives, timber connectors and novel prefabrication methods contributed to the achievement too.

Unfortunately, the maintenance of the hall proved cumbersome and expensive. Amid the economic hardships of the post-1962 socialist period, the structure deteriorated and was eventually torn down around 1980. Squire initially planned for the hall to be built of reinforced concrete. Had that been done, would it still be standing today?

The opening ceremony in 1956 was a notable event in post-war Rangoon. Raglan Squire describes it the following way:

“The Library building I lit from the inside so that all the little coloured glass, coffin-shaped windows sparkled like a Christmas tree. The Assembly Hall was brightly lit inside and we arranged for a gentle flow of lighting outside; the roof looked like the humped back of a giant turtle. The buffet tables each had their own oil lamps, the pweis glittered as on the street on my first night [in Rangoon]—and the whole complex was alive with happy, laughing people. The crowds were so great that we held up the traffic for hours on the main Prome [Pyay] Road out of Rangoon. It was a great day and great evening. I went to bed happy—yet with a little tinge of sadness. Could anything quite so magnificent ever happen again for me, personally, in the rest of my life? I have had many great days since but, truly, never one quite like that.”

In 1961—only five years after it had moved into the brand new building complex —the architecture department was again relocated. This time, the move took it from the indirectly US-funded and British-designed facilities into the newly built Institute of Technology, which—tellingly—was donated by the Soviet Union.

Squire had left Burma a long time before then. Subsequent assignments took him around the world, including the Middle East where he built the Tehran and Bahrain Hilton hotels, an airport in Baghdad and a town-planning scheme for Mosul. Squire had a long retirement and passed away in 2004. His son Michael is the principal of the London-based architectural firm Squire and Partners, whose most notable projects include the Chelsea Barracks and the Shell Centre redevelopment, both in London. His firm should not be confused with the Singaporean heir to Squire’s name, RSP (short for Raglan Squire & Partners, which Squire founded shortly after leaving Burma). The firm continues to be involved in Yangon today, but makes no reference to its founding father on their website. RSP built the Sule Shangri-La in the 1990s and participates in the proliferation of rather nondescript mixed-use developments around Yangon, such as the planned Gems Garden project west of Inya Lake.

While RSP may have strayed, it seems, from the grand designs of its founder, we hope this guide can at least help put to rest a worry that Squire recounts in his autobiography, as he departed from Burma in the 1960s: “I wanted to do something great. I knew I had done a good job in Rangoon but, with Burma slipping into self-imposed obscurity, who on earth would ever see my buildings there?”

U Soe Lin’s Residence

Year built: 2014

Architect: U Soe Lin

Although his major works are further south (City Hall and Myoma National High School), Myanmar’s star architect U Tin and his descendants have had a profound influence on this part of the city, which recurs frequently over the remaining pages of this chapter. U Soe Lin is one of U Tin’s grandsons. His modern residence stands adjacent to the old master’s own house (which unfortunately is off-limits these days). Like many in his family, U Soe Lin followed in his grandfather’s footsteps. He read architecture in the USA in the 1970s, at the University of Oklahoma and at the Catholic University in Washington DC; his practice today is also located in the US capital. U Soe Lin has mainly worked in the United States but makes frequent trips back home, and has built here too. Notable structures include the Pun Hlaing International Hospital, which was finished in 2005. With the boom in Yangon today, he is seeing a rise in assignments in his native Myanmar. Another noteworthy project is the Royal Textile Academy Museum in Bhutan.

U Soe Lin’s Yangon residence is currently rented out to the Danish ambassador. This building perpendicular to Inya Road is one of dualities. It reflects the architect’s roots in Burma as well as his Western training. Being residential, the front of the building is kept private with a gate and stone wall shielding the living quarters. Behind that wall, the house opens up to a landscaped garden with an open terrace. The functional spaces and bedrooms are located in the modern masonry structure, made of reinforced concrete. The side wall features narrow windows. A pavilion area, visible from the outside and covered in glass, contains the living room. Exposed steel supports it, covered by a wooden roof with subtle nods to vernacular temple architecture. It towers above the building section like an umbrella.

Yangon University

Formerly: University of Rangoon

Address: Yangon University Estate

Year built: Established 1920

Architect: Various

Yangon University is one of the most complex and contested spaces in Yangon, one of immeasurable political importance for the history of the city. It is where successive generations of the country’s brightest minds have come together to imagine a better future for themselves and their peers. For that reason, it was also the theatre of many moments of upheaval during Myanmar’s fraught 20th century.

The campus is nestled between Inya Lake and a long stretch of Pyay Road, with some of the more notable buildings concentrated in the area’s northernmost quarter circle. Most tourists drive down Pyay Road on their way from the airport and can make out the set-back buildings through the university’s leafy surroundings. Other buildings, like the University of Medicine-1, are right along the road. A stroll around the campus is highly recommended.

The university consists of a large number of lecture halls and faculty buildings, student hostels, sports facilities, library buildings, a Christian chapel, the Buddhist Congregation Hall as well as a large Convocation Hall. The latter was built in 1927. It sits at the end of a long driveway and serves as a focal point for the sprawling campus.

The Hall’s symmetrical shape, with a stepped back roof and three arched doorways in the centre, creates a stately impression. Both sides of the building feature colonnaded walkways. A large lecture theatre is flooded with natural light, thanks to its glass dome. It was here that US President Barack Obama gave a speech on his state visit to Myanmar in 2012. (In 2014, he delivered a speech in the Diamond Jubilee Hall, also on the campus.) The architect of the Convocation Hall was none other than Thomas Oliphant Foster, who had already designed several buildings in Yangon, some with his junior partner Basil Ward. Ward also helped with work at the university until his return to London in 1930. Besides the Old Library Building (1927), it is likely that Foster and Ward also designed the Science Hall: note its large cantilevered entrance canopy, similar to the National Bank of India’s on Pansodan Street, today’s Myanma Agricultural Development Bank.

Judson Chapel was built in the early 1930s. Its architectural language is similar to that of the Convocation Hall and has clear Art Deco leanings. Its tall tower is the university’s other main landmark. It is named after Burma’s first Baptist missionary, Adoniram Judson (more on him can be read in the Bible Society of Myanmar section). John D Rockefeller, Jr. donated 100,000 rupees for the chapel’s construction.

Burma’s most famous architect, U Tin, also left his mark here—albeit not directly within the university premises. His Buddhist Congregation Hall, opposite University Avenue, is set back from the street and not easily found. Built in trademark U Tin style, it was donated by a wealthy Burmese merchant to offer a Buddhist place of worship to the students. A key keeper is usually around and can let you in. More modern buildings include the Universities’ Central Library, built by one of U Tin’s grandsons. Another of U Tin’s progeny, his youngest son U Kin Maung Thint, built the Recreation Hall around 1960 together with architect and planner Oswald Nagler.

The university was founded by the British as Rangoon College in 1878, then an affiliate of the University of Calcutta. It later became independent and was renamed University College, and later Rangoon University in 1920 after merging with the Baptist Judson College, which gave its name to the aforementioned Judson Chapel.

Teaching at the University was modelled on Oxbridge, as was the case for elite institutions across the British colonies. As historian Jan Morris describes in Stones of Empire: The Buildings of the Raj:

“The greater universities established by the British in India, notably those in the Presidency towns, deliberately set out to transfer British ideas and values to the Indian middle classes, if only to create a useful client caste. Their curricula were altogether divorced from Indian tradition—no more of those thirty-foot kings—and their original buildings were all tinged somehow or other with architectural suggestions of Cam or Isis [these are rivers flowing through Cambridge and Oxford, respectively; the authors].”

This notion easily applies to Rangoon University too. Except that by summoning the country’s brightest minds, it eventually attracted young men who became the leading cadres of the Burmese nationalist movement. Aung San, Ba Maw, U Nu and U Thant all studied here, to name but the most famous examples.

Major strikes took place at the university in 1920, 1936 and 1938. (The 1920 strike is described in some detail in the section about Myoma National High School.) The campus suffered significant damage from bombings during the Second World War.

In 1949, the Karen (who occupy Karen State on the Thai border) made incursions into Rangoon—a sign of post-independence Myanmar’s fragility—and the University was closed down for a time.

After Ne Win’s coup in 1962, a new generation of students were quick to rise up, in July of the very same year. Ne Win was quick to react: he dynamited the student union building in retaliation. The University was put under a military directorate—it was previously run by the professors themselves—and the default language of instruction changed from English to Burmese. While the change to a vernacular and non-elite language could have become a positive development in itself, the military’s rigid and inept approach led to a drastic fall in academic standards.

In 1974, the campus was again the theatre of major student protests when the coffin of U Thant, the former UN Secretary-General, was snatched from Kyaikkasan Race Course and brought to the university. This was an outraged reaction to the regime denying him an official funeral. More about this incident, and its tragic aftermath, can be found in the section on the U Thant Mausoleum. Students from Yangon University were also central to the 1988 uprisings.

Undergraduate degrees were scrapped after student protests in 1996 and only resumed in 2013. The university continues to be a tense political space where students test the limits of authority. In November 2014, hundreds of students protested against an education bill that, they felt, did not give universities the independence previously promised. The education bill continued to spur discontent across the country: in January 2015, around 100 students took part in a two-week march from Mandalay to Yangon—a distance of 650 kilometres.

There was controversy too in December 2014, when around 300 students from Yangon University were not granted diplomas because they did not have “scrutiny cards”, or ID papers—a problem that disproportionately affects Muslim students from Rakhine State, whose right to Burmese citizenship is ferociously contested by the authorities. (The government similarly denies the existence of the ethnic label of “Rohingya”, which many Muslims from Rakhine State self-identify as.) The UN Special Rapporteur for Human Rights in Myanmar, Yanghee Lee, said at the time that she was “shocked” to hear that these students were unsure of receiving their degrees.

At the same time, Myanmar’s opening-up has allowed the University to foster new and encouraging international ties. Notably, a partnership with the University of Oxford is helping it to “develop and implement a strategic plan that will transform the way they teach and research,” according to the British institution.

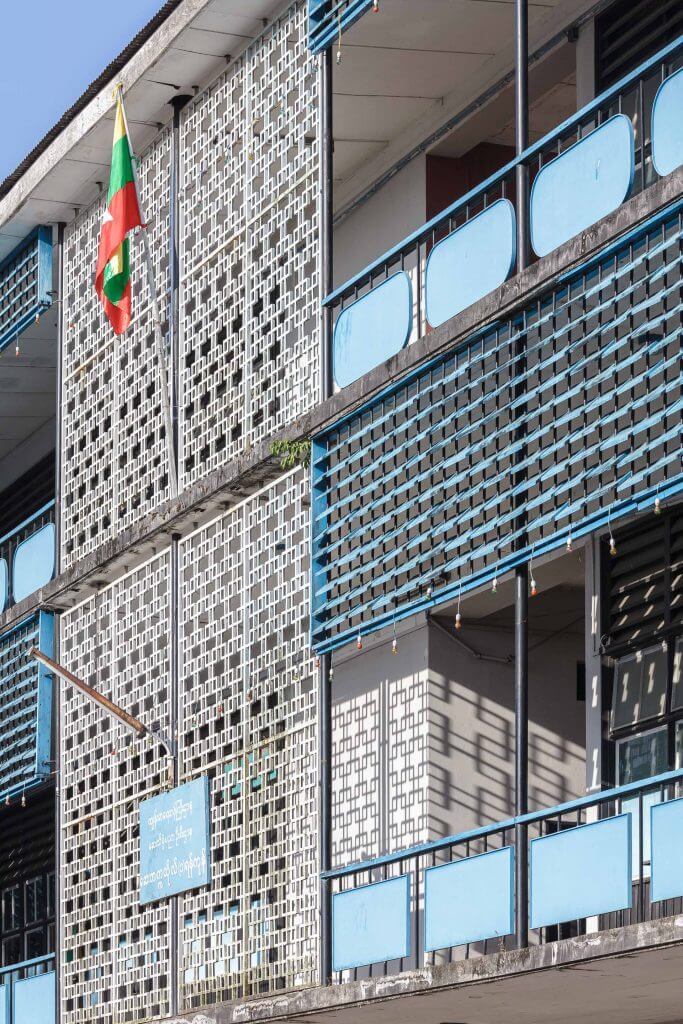

Universities’ Central Library

Address: Yangon University Estate

Year built: 1976

Architect: U Kin Maung Lwin

This modern building, adjacent to the older university library, was designed in 1973 and was due for completion in early 1975. However, the U Thant funeral crisis rocked Rangoon University in 1974 and led to a delay in construction. Students looted the building site, equipping themselves with bricks and other building materials to build a tomb for the remains of U Thant on the grounds of the former Students’ Union building, which was destroyed by the Ne Win Government in 1962.

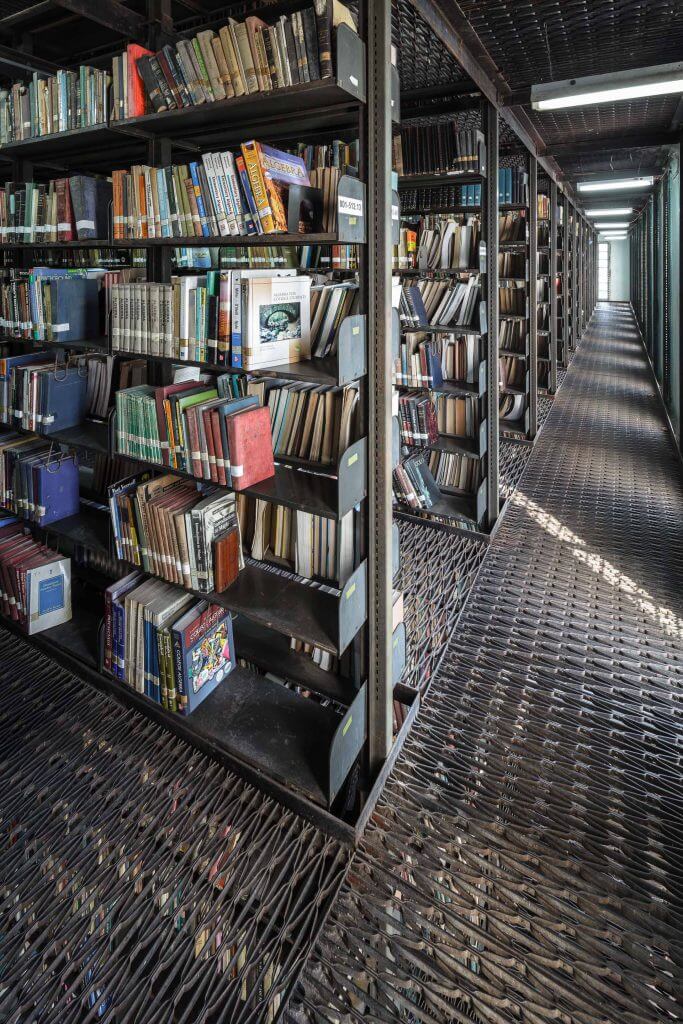

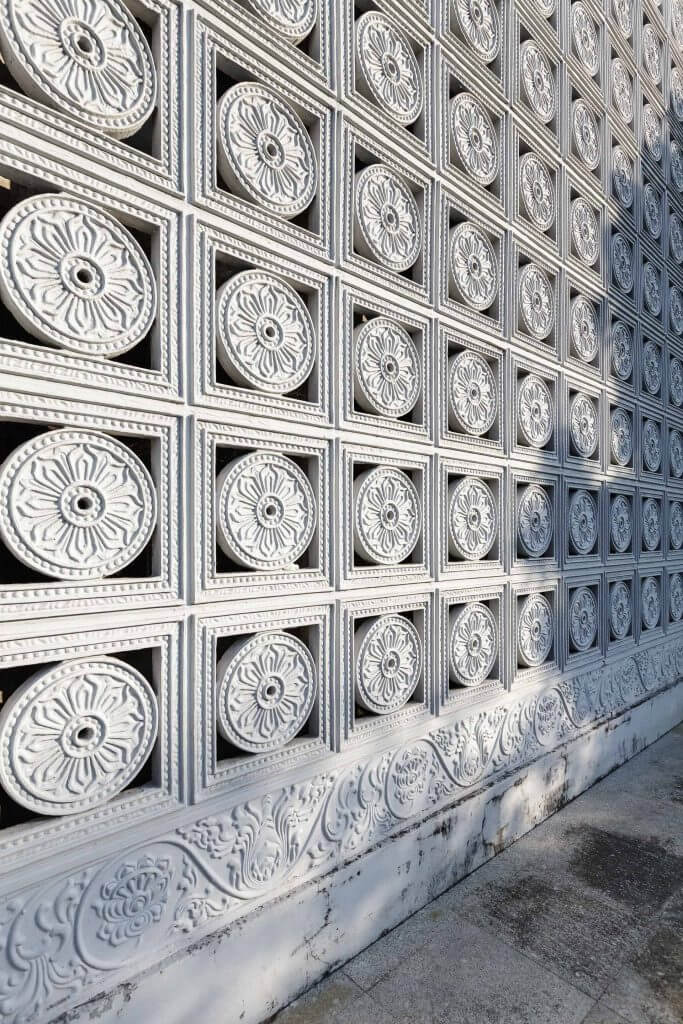

The library building brilliantly showcases “architecture of scarcity”, or the ingenuity of local architects making do with very limited means. Note the windows with their many grilles—large glass was very hard to come by. Simple iron angle bars support the teak stairs. The marble is sourced from inside Myanmar; this local variety is not as shiny as its Mediterranean equivalents. The floral pattern on the outside of the building was supposed to be permeable, allowing for more natural light; but again those plans were shelved as the production proved too cumbersome. The shafts underneath the roof were designed to hold the air conditioning units that, alas, were never procured and fitted. An inner courtyard was repurposed as a light shaft, allegedly because the university authorities wanted to avoid providing a cuddling spot for amorous students. All the while, the building’s airy layout was accomplished successfully. The building’s folded roof is particularly notable and should be renovated in the coming years. The inverted pyramid layout is best appreciated from the first floor. The library design also took great care to preserve many of the local gangaw trees that stood on the site. In the end, only nine were felled, leaving more than 40 standing and offering plenty of shade today. The wide staircase was designed to provide informal seating for the students during their breaks.

Although only designed to hold 280,000 books, the library today possesses 600,000 in the building’s air-conditioned basement. The ground floor is split between a reading room and an administrative office. The first floor contains further post-graduate reading rooms as well as some of the library’s prized antique possessions, including palm leaf books, some more than 500 years old.

The library’s architect U Kin Maung Lwin (or Ronnie, as he is widely known) is a grandson of U Tin, Myanmar’s most famous architect. Together with his friend Dr Kyaw Lat (today YCDC’s chief consultant on urban planning issues), Ronnie studied architecture in Dresden, Germany, setting off first to London by a Bibby Line steamship in 1960. While Dr Kyaw Lat returned permanently to Myanmar in the 1970s, Ronnie settled in West Germany, working for universities and major construction company Holzmann until his retirement. Today he splits his time between his two homes in Yangon and Wetzlar, north of Frankfurt. His grandfather had several children and grandchildren, who include many architects working across the globe in the US, the UK and, in Ronnie’s case, Germany.