Formerly: University of Rangoon

Address: Yangon University Estate

Year built: Established 1920

Architect: Various

Yangon University is one of the most complex and contested spaces in Yangon, one of immeasurable political importance for the history of the city. It is where successive generations of the country’s brightest minds have come together to imagine a better future for themselves and their peers. For that reason, it was also the theatre of many moments of upheaval during Myanmar’s fraught 20th century.

The campus is nestled between Inya Lake and a long stretch of Pyay Road, with some of the more notable buildings concentrated in the area’s northernmost quarter circle. Most tourists drive down Pyay Road on their way from the airport and can make out the set-back buildings through the university’s leafy surroundings. Other buildings, like the University of Medicine-1, are right along the road. A stroll around the campus is highly recommended.

The university consists of a large number of lecture halls and faculty buildings, student hostels, sports facilities, library buildings, a Christian chapel, the Buddhist Congregation Hall as well as a large Convocation Hall. The latter was built in 1927. It sits at the end of a long driveway and serves as a focal point for the sprawling campus.

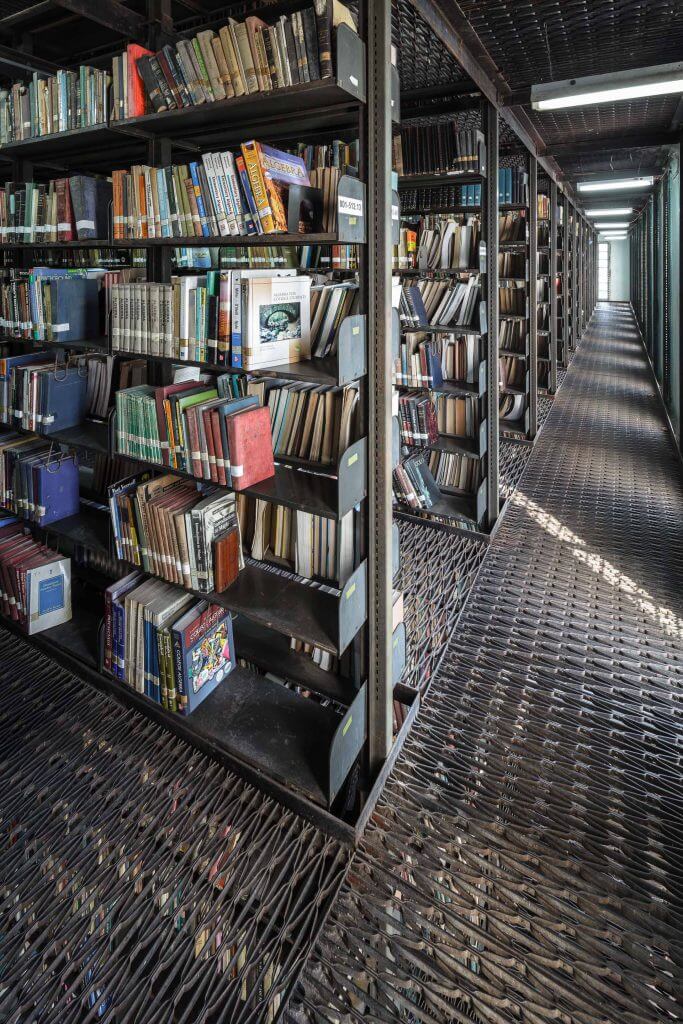

The Hall’s symmetrical shape, with a stepped back roof and three arched doorways in the centre, creates a stately impression. Both sides of the building feature colonnaded walkways. A large lecture theatre is flooded with natural light, thanks to its glass dome. It was here that US President Barack Obama gave a speech on his state visit to Myanmar in 2012. (In 2014, he delivered a speech in the Diamond Jubilee Hall, also on the campus.) The architect of the Convocation Hall was none other than Thomas Oliphant Foster, who had already designed several buildings in Yangon, some with his junior partner Basil Ward. Ward also helped with work at the university until his return to London in 1930. Besides the Old Library Building (1927), it is likely that Foster and Ward also designed the Science Hall: note its large cantilevered entrance canopy, similar to the National Bank of India’s on Pansodan Street, today’s Myanma Agricultural Development Bank.

Judson Chapel was built in the early 1930s. Its architectural language is similar to that of the Convocation Hall and has clear Art Deco leanings. Its tall tower is the university’s other main landmark. It is named after Burma’s first Baptist missionary, Adoniram Judson (more on him can be read in the Bible Society of Myanmar section). John D Rockefeller, Jr. donated 100,000 rupees for the chapel’s construction.

Burma’s most famous architect, U Tin, also left his mark here—albeit not directly within the university premises. His Buddhist Congregation Hall, opposite University Avenue, is set back from the street and not easily found. Built in trademark U Tin style, it was donated by a wealthy Burmese merchant to offer a Buddhist place of worship to the students. A key keeper is usually around and can let you in. More modern buildings include the Universities’ Central Library, built by one of U Tin’s grandsons. Another of U Tin’s progeny, his youngest son U Kin Maung Thint, built the Recreation Hall around 1960 together with architect and planner Oswald Nagler.

The university was founded by the British as Rangoon College in 1878, then an affiliate of the University of Calcutta. It later became independent and was renamed University College, and later Rangoon University in 1920 after merging with the Baptist Judson College, which gave its name to the aforementioned Judson Chapel.

Teaching at the University was modelled on Oxbridge, as was the case for elite institutions across the British colonies. As historian Jan Morris describes in Stones of Empire: The Buildings of the Raj:

“The greater universities established by the British in India, notably those in the Presidency towns, deliberately set out to transfer British ideas and values to the Indian middle classes, if only to create a useful client caste. Their curricula were altogether divorced from Indian tradition—no more of those thirty-foot kings—and their original buildings were all tinged somehow or other with architectural suggestions of Cam or Isis [these are rivers flowing through Cambridge and Oxford, respectively; the authors].”

This notion easily applies to Rangoon University too. Except that by summoning the country’s brightest minds, it eventually attracted young men who became the leading cadres of the Burmese nationalist movement. Aung San, Ba Maw, U Nu and U Thant all studied here, to name but the most famous examples.

Major strikes took place at the university in 1920, 1936 and 1938. (The 1920 strike is described in some detail in the section about Myoma National High School.) The campus suffered significant damage from bombings during the Second World War.

In 1949, the Karen (who occupy Karen State on the Thai border) made incursions into Rangoon—a sign of post-independence Myanmar’s fragility—and the University was closed down for a time.

After Ne Win’s coup in 1962, a new generation of students were quick to rise up, in July of the very same year. Ne Win was quick to react: he dynamited the student union building in retaliation. The University was put under a military directorate—it was previously run by the professors themselves—and the default language of instruction changed from English to Burmese. While the change to a vernacular and non-elite language could have become a positive development in itself, the military’s rigid and inept approach led to a drastic fall in academic standards.

In 1974, the campus was again the theatre of major student protests when the coffin of U Thant, the former UN Secretary-General, was snatched from Kyaikkasan Race Course and brought to the university. This was an outraged reaction to the regime denying him an official funeral. More about this incident, and its tragic aftermath, can be found in the section on the U Thant Mausoleum. Students from Yangon University were also central to the 1988 uprisings.

Undergraduate degrees were scrapped after student protests in 1996 and only resumed in 2013. The university continues to be a tense political space where students test the limits of authority. In November 2014, hundreds of students protested against an education bill that, they felt, did not give universities the independence previously promised. The education bill continued to spur discontent across the country: in January 2015, around 100 students took part in a two-week march from Mandalay to Yangon—a distance of 650 kilometres.

There was controversy too in December 2014, when around 300 students from Yangon University were not granted diplomas because they did not have “scrutiny cards”, or ID papers—a problem that disproportionately affects Muslim students from Rakhine State, whose right to Burmese citizenship is ferociously contested by the authorities. (The government similarly denies the existence of the ethnic label of “Rohingya”, which many Muslims from Rakhine State self-identify as.) The UN Special Rapporteur for Human Rights in Myanmar, Yanghee Lee, said at the time that she was “shocked” to hear that these students were unsure of receiving their degrees.

At the same time, Myanmar’s opening-up has allowed the University to foster new and encouraging international ties. Notably, a partnership with the University of Oxford is helping it to “develop and implement a strategic plan that will transform the way they teach and research,” according to the British institution.

It’s so effective for me.

Thanks u so much ✌