Bogyoke Aung San Stadium

Formerly: Burma Athletic Association Grounds

Address: Zoological Garden Road

Year built: 1930/1958

Architect: Unknown

The Bogyoke Aung San Stadium was once Yangon’s greatest sports stadium, with a capacity of about 40,000. It opened in 1930 as the grounds for the Burma Athletic Association (BAA). After independence in 1953, authorities renamed it to honour Burma’s national hero Aung San. (Bogyoke means general in Burmese.) A PA system and two-storey stand were added in 1958. The stadium was also renovated in 1959–1960 for the second Southeast Asian Peninsular Games, which Yangon hosted in 1961. The games brought together more than 800 athletes from Burma, Cambodia, Laos, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam.

Today the stadium is home to one of the Myanmar National League’s major football clubs, Yangon United FC. The club was founded by ubiquitous tycoon Tay Za, who also owns Air Bagan and has myriads of business interests in the country. His son is the club’s chairman. The league replaced the Myanmar Premier League in 2009 but, like its predecessor, suffers from underfunding and poor facilities. The pitch appears barely playable, especially during the rainy season when a thick layer of water floods the grass. The games are poorly attended. However, the growth of internet access in Myanmar promises a greater audience for football clubs in a football-mad country. On Facebook, YUFC counts several tens of thousands of followers who can watch video clips of the latest match highlights. In 2014, the team had several Brazilian outfield players and an Australian goalkeeper.

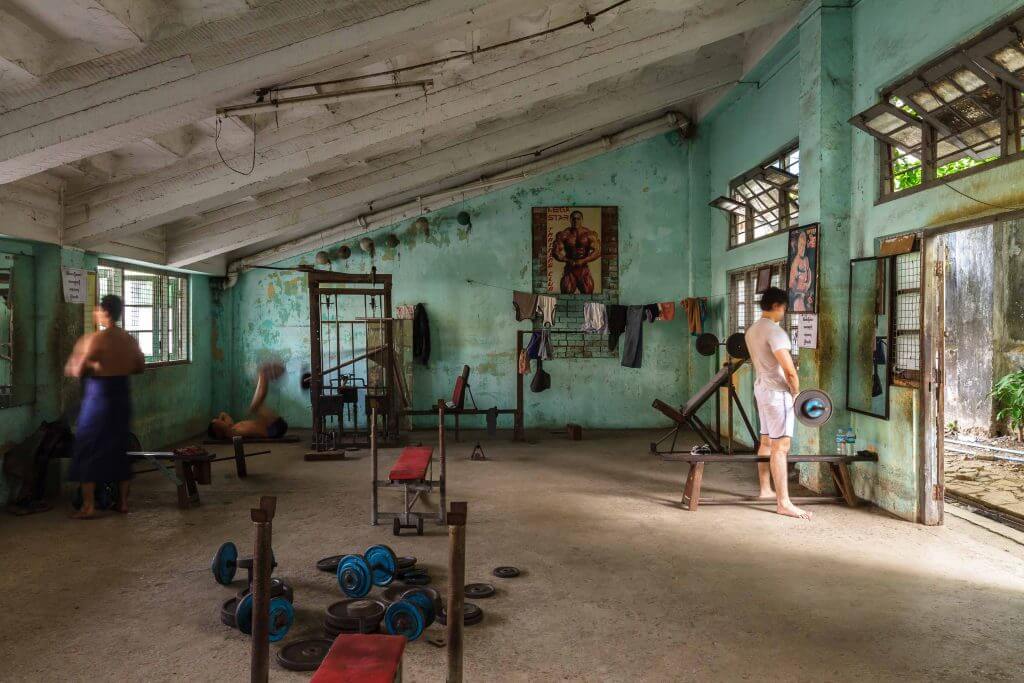

Except during organised events, the ageing sports complex is accessible to the public. It contains small indoor facilities including a gym. An impoverished community lives beneath the stands. The stadium is bordered to the south by ticket stalls for long-distance bus companies. A supermarket, restaurants and other retailers line the stadium to the north. A series of portraits of Aung San and his daughter, Aung San Suu Kyi, feature at the entrances. Can you think of another country where a portrait of the political opposition adorns the country’s biggest football stadium? (Or indeed, any stadium?)

Rose Garden Hotel

Address: 171 Upper Pansodan Road

Year built: 1995-2015

Architect: Unknown

Parts of the hotel still remain under construction at the time of writing and only two floors are being rented out in what the management calls a “soft opening”. Work on this site began as early as the mid-1990s, but was delayed by the Asian financial crisis, suffering similar struggles to the Centrepoint Towers. Once finished, the five-star hotel (financed by a Hong Kong-based investor) will have more than 300 rooms, adding much-needed capacity to Yangon’s market.

Although it gives the impression of belonging to an international chain, this is an independently operated hotel. The rooms on offer are more spacious than those of competitors in the same price range, and tastefully furnished. But—for the time being, at least—you may be unsettled by the hotel’s “construction site” feel: for example, the current entrance leads through a tunnel to the makeshift reception area. The architects deserve credit for their ambition. This is a fearless and exuberant take on Myanmar architecture, differing from the all-too-common faceless tower blocks. Unfortunately, stone-made pyatthat roofs do not convey the same lightness and elegance as traditional temple designs.

On Upper Pansodan Road and only a short walk from Kandawgyi Lake, the hotel is set against the greens of the adjacent Zoological Garden, apart from the hustle and bustle of downtown Yangon. An open sewer in front of the hotel illustrates that infrastructure remains a big challenge in the city.

Queen Supalayat Mausoleum

Address: Shwedagon Pagoda Road

Year built: 1925

Architect: Unknown

The whitewashed brick monument was erected after the death of Burma’s last queen in 1925. It is built in traditional style: the square base containing her ashes is topped by a stone-made imitation of a multi-tiered pyatthat roof. Its top is crowned by a golden hti. The designers may have “wisely divined that Supalayat would be happier in a tomb reflecting the past rather than the present”, as Donald Stadtner writes in his book Sacred Sites of Burma.

Supalayat was born in 1859 and ascended to the throne as King Thibaw’s wife. The two were half-siblings, their father being King Mindon. Unusually for polygamous Burmese royal households, Supalayat was Thibaw’s only wife. This, it was said, could be attributed to the queen’s domineering attitude and stormy temper. Her most notorious acts included the execution of a rival with whom the King had fallen in love and, though she denied knowledge of the plot, the assassination of up to 100 royal family members in one brutal slaughter. The royal family was sent into exile by the British following the Third Anglo–Burmese War in 1885. Along with their three daughters and a small entourage, they ended up in Ratnagiri, halfway between Mumbai and Goa along India’s western coast. Thibaw died here aged only 57. For those interested in a literary account of Burma’s history and the royal family since their 1885 exile, Amitav Ghosh’s The Glass Palace is a pleasing page-turner. Supalayat was permitted to return to Burma in 1919, and spent her last years in seclusion in Yangon, in today’s 24 Komin Kochin Road.

Yangon International Hotel

Address: 330 Ahlone Road

Year built: 1990-1995

Architect: Unknown

The Yangon International Hotel’s construction started in 1990 and finished five years later. Its endless rows of rounded balconies wouldn’t look entirely out of place in Las Vegas.

The Japanese Minatsu Construction Group initially planned a more ambitious project on this site, opposite the People’s Park. During the 1990s, several Japanese firms had their representative offices in this building, which explains the hot bath on the upper terrace, as well as the Japanese restaurant and the karaoke venue on the premises. The location may be the best thing about the hotel. An elevator ride to the ninth floor rewards the intrepid explorer with unhindered access to an airy but largely abandoned roof terrace overlooking this leafy part of Yangon, and affording good views of the Shwedagon Pagoda. The hotel management has begun building an almost identical-looking annex, set to open in 2016.

Karaweik Palace

Address: 152 Bo Myat Tun Road

Year built: 1972-1974

Architect: U Ngwe Hlaing

Returning from the 1970 World Exposition in Osaka (Japan), General Ne Win was so taken with the Burmese pavilion displayed there that he decreed a vast replica be built in Yangon, on Kandawgyi Lake. The Burmese pavilion in Osaka itself was inspired by the Pyi Gyi Mon Royal Barge used by Burmese kings for ceremonial processions in Mandalay, seat of the royal court in the second half of the 19th century. Kandawgyi Lake was created by the British colonial administration to provide clean water to the city. It sources its water from nearby Inya Lake through underground pipes.

Karaweik Palace was built between 1972 and 1974, off the eastern shore of the lake. Its dimensions are impressive (82 × 39 metres). Its gold coating glistens at night, illuminated by massive spotlights. It is bulkier and less delicate than the two versions that inspired it, in Mandalay and Osaka. The name Karaweik is derived from the mythical birds adorning the front of the boat. The seven-tiered pyatthat roof is a classic display of traditional Burmese architecture, echoing the royal palace in Mandalay. A pavilion in front of the palace contains a restaurant hosting dinner shows featuring traditional dances. The venue can also be hired for special celebrations and events.

Karaweik Palace is visible from almost anywhere around the lake, the shore of which is split into two sections accessible to visitors. The larger one contains a few small temples reached by foot along wooden boardwalks. The smaller one features Karaweik Palace, a children’s playground and areas for music festivals. Just like most venues catering to foreign tourists and Yangon’s high society, the Palace was run by the Ministry of Trade before it was leased to a local entrepreneur in the late nineties. Although tourists these days have rather mixed views of the dinner buffets, the Karaweik’s kitchen used to be famous for the quality (and exorbitant prices) of its breads and ice creams. During the violent scenes in August 1988, the Palace’s staff invited monks from nearby monasteries to spend their nights here in safety.