General Post Office

Formerly: Bulloch Brothers & Co.

Address: 39-41 Bo Aung Kyaw Street

Year built: 1908

Architect: AC Martin & Co. (contractors)

This red brick structure first housed the office of Bulloch Brothers & Co., the mighty rice trading firm founded by Scotsmen James and George Bulloch. In the shadow of Calcutta’s port, Rangoon became an ever-growing maritime hub for the Bay of Bengal in the mid-19th century. The Bulloch brothers, working as a loose subsidiary of the British India Steam Navigation Company (BI), became the largest rice-milling and -trading operation in the region. Although BI’s relationship with the Bullochs was tense, they could not afford to alienate these powerful local players.

Six decades after its beginnings on the shores of Sittwe (today the capital of Rakhine State, on Myanmar’s western coast) in 1840, Bulloch Brothers & Co. commissioned this spacious and elegant building along Strand Road. The design and cream colour of the Lancet-arched windows and ornate stuccowork give the building its distinctive feel. The front, southern side of the building recently enjoyed a fresh lick of paint, with the mortar gaps accentuated with white coating (unlike the other sides). The stunning beaux-arts iron portico is one of the last, if not the last, of its kind in Yangon.

Bulloch Brothers & Co. was liquidated in 1933 (although some records show the company trading in some form until the outbreak of the Second World War). At around the same time, the General Post Office suffered terrible damage in the 1930 earthquake. It was a graceful, if delicate, filigreed building with nods to Buddhist architecture. The global ripples of the Great Depression meant plans for a new and improved version were set aside. The Bulloch Brothers building was acquired and repurposed instead.

Anyone can venture into the General Post Office today and walk around. The railings of the double-winged stairways are beautifully ornate. The wooden stairs appear to be the original ones, judging by their pattern of wear and the way they creak under your step. The interior mixes some clearly original wooden counters with some new office space made of plastic and steel.

At around the time the building became the new General Post Office, a young man named Shu Maung failed his medical exams and began work here as a postal clerk. He was also active in the nationalist struggle and, the story goes, used his job to intercept British letters of strategic relevance. When he rose to become a founding cadre of the Burmese Independence Army, he chose a nom de guerre—Ne Win—that would echo through the ages.

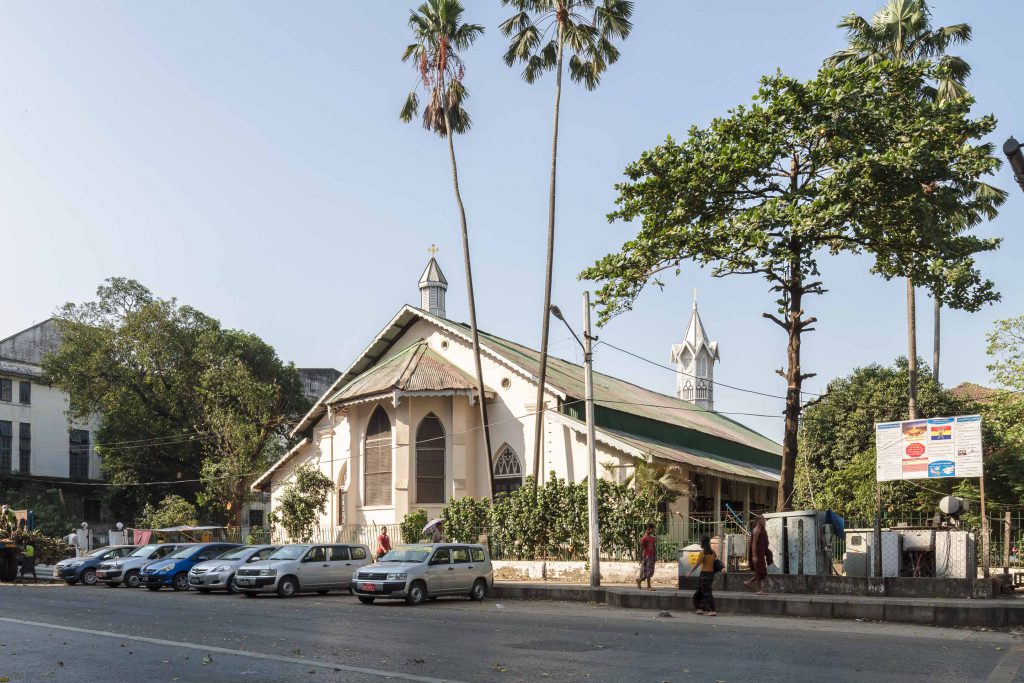

Armenian Apostolic Church of St John the Baptist

Address: 66 Bo Aung Kyaw Street

Year built: 1863

Architect: Unknown

This is the oldest church in Yangon today. It was built in 1862 and consecrated as the Church of St John the Baptist a year later. The Armenian community first came to Burma from Persia in the 17th century, long before the onset of British colonisation. Sharman Minus, an Armenian genealogy enthusiast, has records of a previous Armenian church “with local bricks and a wooden spire” that stood on the grounds of today’s High Court in 1766.

Today’s church is certainly an improvement on its predecessor, but still modest. It has arched windows and a bell, which is rung by hand. The building features a covered entrance and cane-seated pews to relieve worshippers during months of searing heat. Besides the altar, with its typically Orthodox depictions of Biblical scenes, the church is sparsely decorated. The makeshift corrugated iron roof, a common feature in this weather-battered city, looks like a temporary solution until repairs can occur. The roof had previously suffered from Japanese shelling in the Second World War.

As noted in our description of Balthazar’s Building, the country’s last Armenian, Basil Martin (a descendent of AC Martin, who built several of the edifices in this book) passed away in May 2013. His death prompted a surge of interest in the otherwise quiet church. It led the to first-ever trip to Yangon by the head of the Armenian Church in October 2014. For Supreme Patriarch Karekin II’s visit, the Yangon Heritage Trust (YHT) unveiled a blue plaque at the entrance, noting the church’s historical significance. Inside the church, the YHT also installed storyboards explaining the history and role of Armenians in Myanmar. Karekin II’s visit, however, had a more urgent motive than simply to remember Myanmar’s Armenians. In an extraordinary tale, he visited effectively to evict the Anglican “priest” in charge, John Felix. As the BBC reported at the time, Felix came across “as a very pleasant, humble man, but unfortunately the Anglican Church says he has never been a priest”. When Karekin II delivered his sermon in St John’s, Sharman Minus, who was in the congregation, sensed something was afoot. Then Karekin announced: “Mr Felix is not a priest, neither Armenian nor Anglican. Therefore, according to the canons of the Armenian Church and the Traditional Churches, any sacrament officiated by him is not valid. We call on Mr Felix exhorting him to stop violating Church Canons and Holy Traditions and insulting the Armenian Church and nation.”

After this episode, John Felix refused to vacate the house he occupied on the grounds. He was eventually evicted, and private security guards patrol the church grounds today. There were further allegations that Felix was using his ill-gotten position for financial gain. The Armenian Church now fly in an Orthodox priest from India for the weekly service.

Mahatma Gandhi Hall

Formerly: Rangoon Times Building

Address: Merchant Road / Bo Aung Kyaw Street

Year built: Unknown

Architect: Unknown

The Rangoon Times was colonial Burma’s oldest English-language newspaper. This three-storey building was its main office at the turn of the 20th century. The paper’s circulation was always small—as was, in fact, Rangoon’s European population. Founded in 1856, it changed hands a few times and went from weekly to daily publishing. In the early 20th century, the newspaper was run by S Williams, who previously opened the first Reuters office in Burma, then located in the brand-new Sofaer’s Building. The Rangoon Times continued to be published until the retreat of British forces from the city in 1942.

In 1951, a few years after independence, this building was purchased by the first Indian ambassador to Burma, MA Rauf. He rechristened it Mahatma Gandhi Hall. It was used mainly for religious, social, intellectual and political gatherings over the following decades.

In July 1990, Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) issued its “Gandhi Hall Declaration” after convening here. Having won a stunning victory at the polls just months before, the junta chose not to recognise the results (even though the elections were their idea). A large crowd greeted the NLD leaders and listened intently as the declaration was read out in front of the building. Heavily armed security forces were on standby next to them. The declaration called for a power transition and the release of jailed members of the party. The call went unheeded. The junta proceeded to annul the vote and declared its sole legitimacy in ruling the country.

More recently, Gandhi Hall was in the news when the trustees unveiled their plans to destroy the building and replace it with a new condominium. The Yangon Heritage Trust (YHT) intervened and lobbied—successfully—for the Hall’s preservation. The bid was supported by the Yangon City Development Committee and the Indian Embassy.

Today the country’s main English newspaper is the Myanmar Times. (Its offices are across from St Mary’s Cathedral.) It was founded by a larger-than-life media entrepreneur from Australia, Ross Dunkley, who also owns the Phnom Penh Post in Cambodia. Thanks to connections with Burmese authorities, Dunkley was able to found the Myanmar Times as a joint venture with local businessman U Sonny Swe. Swe sold his shares in 2006; he now runs a rival publication, Mizzima. Dunkley was briefly imprisoned in 2011 amid what was deemed to be an internal power struggle with Dr Tun Tin Oo, the Burmese shareholder who replaced Swe. (In late 2014, prominent businessman U Thein Tun took a majority share in the paper.)

YCDC Bank

Formerly: A Scott & Co.

Address: 526-532 Merchant Road

Year built: 1902

Architect: Unknown

This three-storey building is diagonally across from Sofaer’s Building. It still bears the name of the original owners and the year of its construction on the pediment facing the street. The building’s façade and its elaborate cornice above the second floor are worth admiring.

A Scott & Co. was a trading house with Scottish roots. Like most of its peers, the firm engaged in a wide range of activities: they were famous for exporting cheroots (Burmese cigars) back to Britain, which were popular at the time. In the 1920s, witty commentators described Rangoon as “a suburb of Glasgow, commercially”. Five of the eight members of the Rangoon Chamber of Commerce in 1910 were Scots. Their firms were central to the colonial economy and commissioned many of 20th-century Rangoon’s most imposing buildings, such as Graham & Co. (today’s British Embassy), Finlay, Fleming & Co. (better known as the former Myanma Oil and Gas Enterprise Building) and the Irrawaddy Flotilla Co. (today’s Inland Waterways Department). Nowadays, the A Scott & Co. building serves as the bank of the Yangon City Development Committee. The three long porticos are prime, shaded spots for cars and hawkers.

Embassy of India

Formerly: Oriental Life Assurance Building

Address: 545-547 Merchant Road

Year built: 1914

Architect: Unknown

This building began as the offices of the Oriental Life Assurance Company, founded in Calcutta in 1818. The firm served European clients almost exclusively and offered an indispensable service, as colonial postings had high mortality rates due to the climate, tropical diseases and poor medical infrastructure in such far-flung corners of the Empire. Tellingly, the few companies that deigned to insure the local population adopted overtly discriminatory policies: the premiums were usually much higher than those levied on Europeans.

Large trees make this whitewashed building difficult to appreciate in its entirety from the Merchant Road side. It is tall for Yangon’s heritage buildings, measuring six floors from bottom to top. The building’s site is narrow but deep. The demolition of the American Baptist Mission Press building, across the road from 36th Street, has cleared up the space for now and you can enjoy a better view from the idle site.

The Indian Embassy moved into the premises in May 1957. By this time, many Indians had already left the country ahead of the Japanese invasion in 1942. As colonial order broke down in the wake of the aerial bombardments of December 1941, Indians became increasingly concerned for their safety. Many still remembered the bloody riots of the 1930s, which pitted striking Indian dockworkers against their Burmese replacements. This perceived threat—many Indians remained in Burma and were not targeted after the British withdrawal—caused hundreds of thousands to embark on a long and arduous overland trek northwards, to India. The writer Amitav Ghosh collected several accounts of those who took part in his 1942 Burma Exodus Archives (available online, on the author’s blog). Collectively they shed light on one of the lesser-known forced migrations of wartime Asia.

Upon seizing power in 1962, Ne Win’s nationalisation drive led to the expropriation of Indian assets and the expulsion of several hundreds of thousands of Indians. The embassy helped with the logistics of yet another large-scale, and again, little-known forced migration. Planes were chartered and “Burma Colonies” in large Indian cities sprang up, housing the so-called “Burma Repatriates”.

Indian–Burmese bilateral relations have warmed considerably since the mid-1990s. They reached rock bottom when India supported pro-democracy activists in the wake of the 1988 uprising. The pro-democracy publication Mizzima, now based in Yangon, was founded in exile in India. Recently the much-touted “Asian Crossroads” linking China with India via Myanmar have created renewed interest in economic cooperation, with a port and special economic zone in Sittwe designed to better connect India’s less-developed northwestern states to the Indian Ocean. The Indian Embassy was renovated in 1999–2000. Embassy staff today still assist Myanmar’s stateless inhabitants of Indian ancestry with obtaining Indian citizenship. A nationwide census was carried out recently; it could help to ascertain just how many stateless “Persons of Indian Origin” (PIO) there are in Myanmar today. However, details have not been published yet for fear of political repercussions. Some estimates put the number of PIOs with neither a Myanmar nor Indian passport as high as one million.

Myanma Foreign Trade Bank

Formerly: Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation

Address: 564 Mahabandoola Garden Street

Year built: 1901

Architect: Unknown

This former building of the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC) was once a Catholic church, creating one of Rangoon’s more spectacular—and unusual—corporate buildings of the early 20th century. Not much of this early splendour remains. The building underwent drastic renovations, most likely in the 1920s, to expand and update the premises. It was stripped of its rich Gothic ornaments and the church spire that once rested on the hexagonal tower. The former HSBC office now resembles a sparse, almost fortress-like building. The tight iron bars on the windows reinforce this impression.

HSBC opened this Rangoon branch in 1901. (It had opened its first office nine years before, on Bank Street.) At the time the bank was a pillar of the British Empire in Asia. While it was chartered under British banking regulations, its opulent headquarters were in Hong Kong. In Fiery Dragons: Banks, Moneylenders and Microfinance in Burma, economist Sean Turnell explains that HSBC’s operations in Burma were relatively minor compared to elsewhere in the Empire. And while HSBC worked with Chettiar moneylenders in Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka), it had little involvement with the Chettiars of Burma, despite their central role in the colonial financial system. Although Rangoon was a minor branch, it was deemed a desirable posting for ambitious young bankers.

Today the HSBC building, along with the building next to it on Mahabandoola Garden Street (with its new and questionable glass façade), belong to the Myanma Foreign Trade Bank (MFTB), one of the country’s major state-owned banks. As the name implies, the MFTB facilitates foreign trade and used to be the sole conduit for foreign exchange transactions. The role of the MFTB and other state banks is in flux today, given Myanmar’s gradual opening-up. Foreign exchange dealings were liberalised in 2012. The country’s currency, the kyat, is now traded relatively freely. Foreign banks are returning: at the time of writing, more than 40 international banks have representative offices in Yangon. In October 2014, nine of these were awarded limited licences to provide banking services, but HSBC was not among them. Nor have they, as yet, re-opened an office.

Former US Embassy

Formerly: Balthazar & Son

Address: 581 Merchant Road

Year built: 1926

Architect: Unknown

With business flourishing, Balthazar & Son expanded onto these adjacent premises on Merchant Road. This is clearly a more modern building, yet the design imitates its older red brick neighbour. Thanks to long-term use as an embassy, it has been regularly maintained and is in rather good shape today. It is simple and stately, with three floors and a bulky cut-stone portico greeting its visitors. The former tenants made some alterations, including tight window grilles on the ground floor and two walled-up windows on the third floor. Large antennas on the top floor hint at the building’s previous diplomatic functions.

The US Embassy moved into these premises soon after Burmese independence. Burma was of utmost strategic interest to the Americans, who feared the spread of Communism in the region. They helped the Chinese Kuomintang regroup in the north of Burma, following their defeat by the Communist Party in the late 1940s. They supported preparations for a counterattack on Kunming, but this plan failed to materialise. As an unintended consequence, parts of Shan State became a hiding ground for these Chinese rebels, which led to the growing cultivation of poppy in the region. This haunts the Golden Triangle (the remote border areas between Myanmar, Laos and Thailand) to this day. Although the US ambassador at the time, William Sebald, denied knowledge of covert CIA operations on Burmese soil, Burmese Prime Minister U Nu was enraged and threatened to sever diplomatic ties between the countries.

In 1988, embassy staff witnessed the dramatic uprisings outside their window. When Burmese security forces opened fire on the demonstrators, Ambassador Burton Levin ordered the Marine Guards to open the door and let civilians seek shelter inside the grounds. The US did not replace Levin when he retired in 1990, reflecting the frosty bilateral relations that followed. A chargé d’affaires was to represent the United States in the following years. In 2012, Derek Mitchell was appointed the new US ambassador and Myanmar has become an important facet of the Obama Administration’s stated “pivot to Asia”. President Barack Obama visited the country in 2012 and 2014, both times delivering speeches at Yangon University. The administration began lifting sanctions on Myanmar in 2012 and is pouring aid money into the country, including in sectors that would have been inconceivable to support before 2011. For example, in 2014, the US aid agency committed to spending an eye-catching 20 million US dollars on “strengthening civil society and the media” in the country.

Myanma Port Authority

Formerly: Port Trust Office

Address: 10 Pansodan Street

Year built: 1926–1928

Architect: Foster & Ward (architects), Clark & Greig (contractors)

The Port Authority’s corner tower is a Yangon landmark. The pitched red tile roof and hand-painted lettering dominate the view from the river and the port. The Corinthian double columns frame arched openings. The enclosed space is covered with green patterns that protect the recessed windows from exposure to the sun. Between the arches, round medallions depict various ships. The entrance is covered by a beautiful entrance canopy similar to the other buildings on this stretch of Pansodan Street. It is slightly arched, increasing its structural height. A recently constructed pedestrian overpass obscures the view of the building from the Strand Road side. While this may be a good thing for pedestrians and traffic flow on this busy thoroughfare, the visual impact is scarring.

In the late 19th century, Rangoon’s port became one of the busiest in the British Empire. To reflect its growing importance, the old Port Authority on this site was demolished and replaced with this more spacious and modern building. The architect, Thomas Oliphant Foster (1881–1942), was the Government of Burma’s Consulting Architect between 1916 and 1920. His two flagship buildings in today’s Yangon are the Port Authority and the nearby Yangon Division Office Complex. Both reflect a modern and monumental architectural style. This relied heavily on imported steel framing and reinforced concrete.

Burma’s chief commodities, rice and teak, were handled in the large wharfs facing the Yangon River. A huge flow of people passed across the jetties. For a time, it was the busiest port in the world. In Crossing the Bay of Bengal, Sunil Amrith quotes a British official who said in 1933: “Until recently second only to New York in importance as an immigration port, Rangoon now occupies pride of place as the first immigration and emigration port of the world.” Most of these passengers were Indian. They became one of the world’s greatest but least-known migrations. According to estimates, around 28 million people crossed the Bay in both directions between 1840 and 1940. Half of that human traffic involved Burma. It was common for Indian labourers to stay for three rice-growing seasons before returning home. Many stayed behind though, and quickly became Rangoon’s largest demographic group. In 1881, the Burmese outnumbered Hindus and Muslims from India. But just 30 years later, there were nearly two Indians for each Burmese.

The Port Authority still operates today. Its tasks include the maintenance of the harbour infrastructure such as moorings, wharfs and jetties. With the opening of the country and increases in cargo traffic, major investments are under way in special economic zones. The nearest to Yangon is Thilawa, about 20 kilometres south of the city. It’s a controversial project. Locals complain that this joint venture with Japan’s aid agency JICA has forced people off their land with little consultation and meagre compensation.

Innwa Bank

Formerly: Mercantile Bank of India, S. Oppenheimer & Co.

Address: 550-556 Merchant Road

Year built: Unknown

Architect: Unknown

Here are two former bank buildings with distinct looks. The left one is the former head office of the Mercantile Bank of India. Its weathered façade is covered with mildew, moss and weeds. Don’t think, however, that this is due to decade-long neglect: the façade looked almost as good as new less than 10 years ago. The heat and monsoon take their toll each year, especially for buildings with a windward façade. This requires more frequent cleaning, or at least more weather-resistant paint. And yet the building still exudes some of the grandeur it shares with the other banks on this street. Stately square columns wrap around the loggia on the third floor. The portico, grilles and balustrades are made of iron and painted in baby blue.

The Mercantile Bank of India was, despite its name, a British undertaking. It was often jokingly referred to as the “Mercantile Bank of Scotland” because of its large contingent of Scottish staff. It mainly financed international trade. The Burmese Innwa Bank took over the premises in the 1990s.

The building on the right is the former S Oppenheimer building, which dates back to the late 19th century. It was recently renovated. The wrought-iron fence and window bars on the ground floor have been replaced with the cheap-looking, shiny metal versions you find throughout the region. Inexplicably, the drainpipes of the awning are now made of blue plastic. Two ATM booths (almost non-existent in Yangon prior to 2012) jut out towards the pavement. In the early 20th century, the third-floor main window extended up to the arch. It was adorned with stained glass. Originally the building featured an iron portico, which was later replaced by two concrete ones. The narrow arcade, which rests on four Corinthian columns, is a relatively recent addition despite its looks.

S Oppenheimer acquired the property in 1893 to cope with a rapidly expanding business. The company, whose roots are German, traded in goods as diverse as police uniforms, elephant gear and famous Underwood typewriters. After a 2011 renovation, Innwa moved into these premises.

Centrepoint Towers

Address: 65 Sule Pagoda Road

Year built: 1995-2014

Architect: Unknown

At the time of writing, this much-maligned construction project is lurching to its conclusion. Many bemoan its architectural banality and overbearing presence in the city centre. Others breathe a sigh of relief that this 20-year, on-and-off construction is coming to an end.

The complex consists of two towers of about 90 metres each. Standing on Sule Pagoda Road’s southern edge, they overlook Mahabandoola Park and afford spectacular views (many of this book’s aerial photos were taken there). The southern tower’s façade is covered with large white tiles, which are reflected in the northern tower’s blue solar glazing. Both towers evoke a rather tired architectural language of the 1990s, unsurprising given the project’s drawn-out genesis.

With a helicopter deck on one rooftop, will private companies offer their rich customers private air taxi services in the not-so-distant future? This might not be far-fetched, given Yangon’s increasingly sclerotic traffic conditions.

The deal to build this mixed-use project occurred as early as 1993 and construction began two years later. One of the towers was intended to be a luxury hotel operated by the Sofitel Group. The other was earmarked for office and retail space. The Thailand-based investor mothballed the project in the wake of the Asian financial crisis in 1998. It stood idle in a semi-finished state for several years until construction resumed in 2005. By 2009, the investors had to inject another 12.5 million US dollars into the project, taking the overall investment beyond 100 million. This makes it one of Yangon’s priciest real estate projects to date. (To put this into perspective, Yoma’s “Landmark” project surrounding the former Myanmar Railways Company will cost an estimated of 500 million US dollars, embodying growing investor confidence in Myanmar.)

After a considerable period searching for the right partner, the Hilton Group was chosen as the hotel operator in 2013. With 300 rooms, it will add considerable capacity to the city’s five-star segment. While the likes of the Canadian Embassy and the Associated Press have already moved into the office tower, the hotel is taking longer than expected. The opening date has been postponed more than once already. The Centrepoint saga isn’t over just yet …