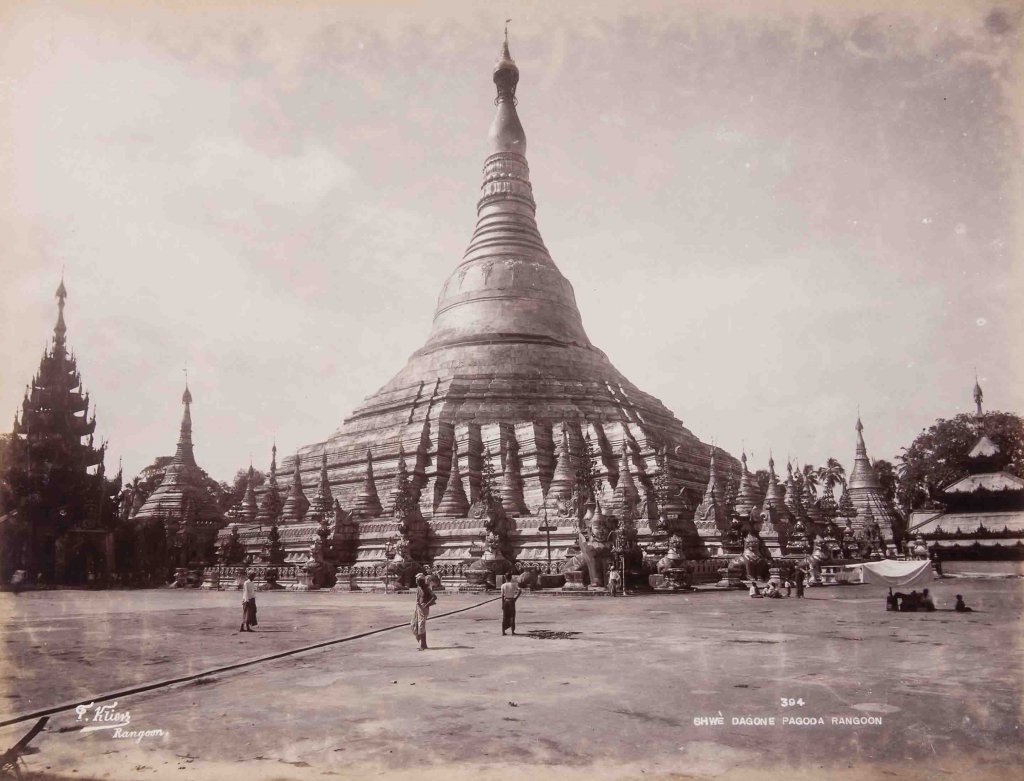

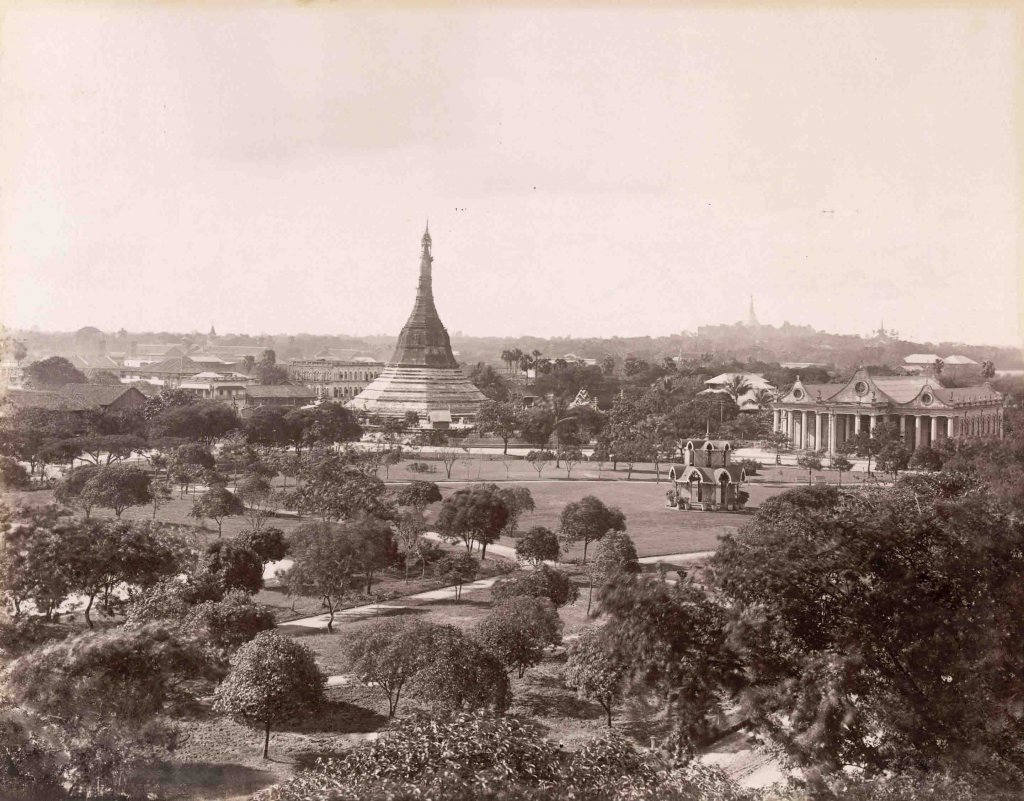

Circa 600 BC

According to the ancient legends, King Okkalapa begins work on the Shwedagon Pagoda.

6-10th century AD

This is the more likely time period for the Shwedagon’s construction, by the Mon people, who reside in present-day Mon State in southeast Myanmar. They also founded the fishing village of Dagon during this period.

1587

Ralph Fitch, a merchant, is the first documented Englishman to set foot in Dagon. He describes the Shwedagon Pagoda as the “fairest place, as I suppose, that is in the world.” However, with his trader’s mindset, he also notes that if the locals “did not consume their golde in these vanities, it would be very plentifull and […] cheape”.

1612

The first Armenian traders arrive in Syriam (today’s Thanlyin, on the opposite banks of what was then Dagon), heralding the start of the city’s long cosmopolitan heritage. The Armenian Church is the oldest church in the city today, built in 1862. Its predecessor, Yangon’s first-ever church, was built in 1766 along the river shores.

1619

The British East India Company, founded 20 years prior, establishes its first outposts in Myanmar—at Ava, Bhama, Prome and Syriam, dealing in Burmese ivory, oil and timber.

1752

King Alaungpaya founds the Konbaung Dynasty, which unites and rules Burma.

1755

Alaungpaya captures Dagon during his invasion of Lower Burma. He adds several other settlements to the village and renames it Yangon, most commonly translated as “the end of strife”.

1824-1826

First Anglo–Burmese War: in 1823 the Burmese Kingdom occupies Shalpuri Island off the coast of Chittagong, in present-day Bangladesh. As the East India Company previously staked a claim to the island, the incident provides a convenient casus belli for the conflict, which would last two years and cost 15,000 European and Indian soldiers their lives. The Burmese death toll is not known. The war ends in British victory, forcing Burma into a commercial treaty and relinquishing significant swathes of territory from Assam (in northern India) to Arakan (today’s Rakhine State, in Myanmar)—but Yangon remains in Burmese hands.

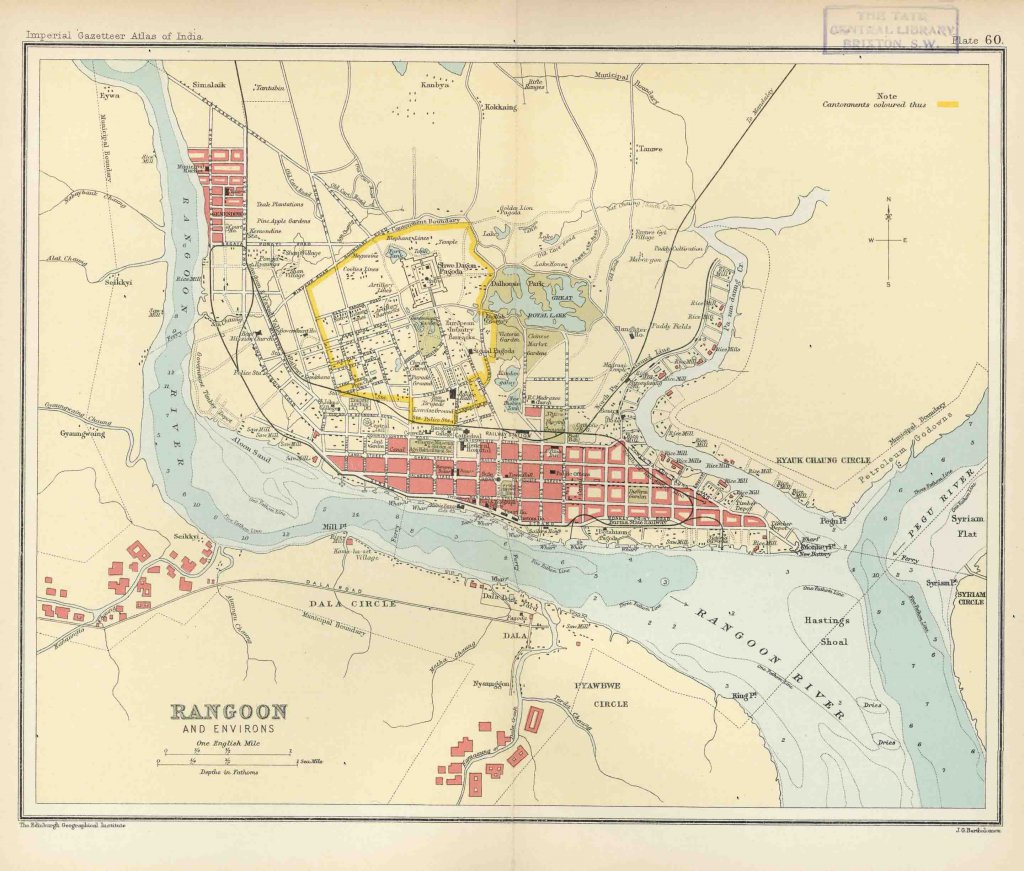

1852

Second Anglo–Burmese War: Commodore George Lambert blockades Yangon’s port in retaliation for perceived breaches of the 1826 treaty. The war ensues, lasting only a few months, and results in the East India Company’s annexation of Pegu province, which became Lower Burma—and including Yangon, now officially Rangoon.

1885

Third Anglo–Burmese War: in a conflict lasting less than a month, the British take control of Upper Burma in the wake of concerns that Burma’s King Thibaw had plotted an alliance with the French. The war completes Britain’s annexation of Burma. They make Rangoon its capital. (Thibaw, Burma’s last king, is exiled to Ratnagiri, in India, where he dies in 1916. His wife, Supayalat, returns to Yangon in 1919. Her mausoleum is featured in this book.)

1914-1918

First World War: while the war does not reach Burma, it has an economic impact on the cash-strapped colonial administration. Construction of the City Hall, for example, is halted during this period.

1920

In one of the first major acts of local resistance to British colonial rule in Burma, students in Rangoon launch a “Universities Boycott”, protesting the British education system’s exclusiveness and high costs.

1930

An earthquake of magnitude 7.3, later dubbed the Pegu earthquake, rocks Rangoon and causes damage to many buildings around town, including the Secretariat, causing it to lose 10 of its 18 towers.

1935

The British Parliament passes the Government of Burma Act, which formally splits Burma from India within the British Empire, and devolves greater power to Rangoon. It comes into force in 1937.

1939

Second World War begins.

1940

Japan offers its support to the Burmese nationalist cause, led by a young man named Aung San. He and his “30 Comrades” make repeated visits to Japan for military training over the following three years.

1941

On 8 March, Rangoon falls to a ground invasion from Japanese forces and their allied Burmese nationalists, led by General Aung San.

Several hundreds of thousands of Indian migrants flee Rangoon overland, fearful for their future in a city no longer under British control.

1944

Growing disillusioned with the merits of Japanese support, due to both broken promises and their failure to stem the tide turning in favour of the Allied Forces, General Aung San decides to change sides.

The Allies re-capture Rangoon in December 1944.

1945

Second World War ends.

1947

In January, General Aung San travels to London to negotiate the terms of Burmese independence with Clement Attlee, the British prime minister.

On 29 July a gang of gunmen, instructed by one of Aung San’s rivals, storm the Secretariat and murder Aung San along with six of his cabinet ministers and two other people. Today the victims are commemorated at the Martyrs’ Mausoleum. Its nine concrete slabs commemorate those killed on that day.

1948

On 4 January, the Union of Burma gains independence.

1949

The government, based in Rangoon’s Secretariat, struggles to keep the country together: armed groups representing each ethnic minority try to strengthen their leverage over the new government through force. A Karen rebellion actually reaches Insein, in the city’s northern suburbs. The Karens are eventually pushed back. (The Burmese army, or Tatmadaw, remain at war with the nation’s myriad ethnic armed groups—this is the longest-running civil war in modern history.)

1954-1956

Independent Burma’s first prime minister, U Nu, convenes the Sixth Great Buddhist Synod at the purpose-built Kaba Aye complex. The synod, lasting two years, brings together 2,500 monks from countries practising the Theravada branch of Buddhism, including Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Thailand.

1962

General Ne Win stages a military coup d’état, marking the start of a long period of army-led dictatorship dressed in socialist rhetoric.

1974

Former UN Secretary-General U Thant, a Burmese diplomat, passes away in New York. Ne Win’s decision not to grant him a state funeral provokes the “U Thant funeral crisis”, which ultimately leads to the construction of the U Thant Mausoleum and major altercations between the army and Rangoon’s students. Scores of students lose their lives.

1988

The pro-democracy “8888 uprising” begins, marking a period of riots, demonstrations and the rise to prominence of Nobel Peace Prize laureate and opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi, none other than Aung San’s daughter.

General Ne Win resigns in July.

In September, the military-run State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) takes control of the country. They embark on an ambitious public works programme in Yangon, designed to dissuade and more effectively quash further unrest—this is detailed in the inset about post-88 changes to the city.

1989

Aung San Suu Kyi is placed under house arrest. She will spend 15 of the ensuing 21 years in detention in her University Avenue residence, only freed from 1995 to 2000 and 2002 to 2003. She was most recently released in November 2010.

1990

Having ceded to Aung San Suu Kyi’s demands for democratic elections, these are staged on 27 May. Her party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), wins convincingly—although she could not participate herself. The military refuses to recognise the result.

1996

Yangon’s municipal body, the Yangon City Development Committee (YCDC), designates 189 heritage buildings in the city. The junta declares the “Visit Myanmar Year” in an attempt to attract more foreign investment and tourists. Aung San Suu Kyi supports a boycott of the country.

1997

Myanmar is admitted to the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN). SLORC is renamed State Peace and Development Council (SPDC).

2005

On 6 November, the government moves the country’s capital from Yangon to Naypyidaw, 300 kilometres to the north. More about this can be read in the dedicated inset.

2007

In one of the pro-democracy movement’s largest and most iconic protests, up to 50,000 demonstrators, led by thousands of robed monks, take to the streets of Yangon between August and October. The images of the military crackdown shock the world.

2008

Cyclone Nargis, the worst natural disaster in the recorded history of Myanmar, kills more than 100,000 people across the country and turns Yangon into a disaster area. Many buildings around the city still bear the scars, exhibiting permanent damage or makeshift repairs.

While the cyclone rages, the military regime refuse to delay a scheduled referendum on their proposal for a new constitution. According to the junta’s tally, 92.8% of the population voted in favour. The constitution provides for general elections, scheduled in 2010, and a nominal return to civilian rule.

2010

On 7 November, Thein Sein, a former military general and prime minister, wins the general election with more than 75% of the vote. He becomes Myanmar’s first civilian president since Ne Win’s coup in 1962.

On 13 November, Aung San Suu Kyi is released from house arrest.

2012

On 1 April, Aung San Suu Kyi is elected to parliament in by-elections.

2014

In December, the YCDC holds its first municipal council elections. These are marred by low turnout and a controversial “one vote per household” rule.

2015

At the time of writing, general elections were being planned for late October or early November. These were heralded as the next big test for Myanmar’s “opening-up”. Aung San Suu Kyi remains constitutionally barred from becoming president—an issue seen by many in Myanmar, and around the world, as a major blemish on the government’s reform efforts.

It was on 1947 19th of July, not 29th of July when General Aung San and his other eight people were murdered.