Former Ministry of Hotels and Tourism

Formerly: Fytche Square Building

Address: 77–91 Sule Pagoda Road

Year built: 1905

Architect: Thomas Swales

This three-storeyed building is 90 metres wide and displays an impressive, ornate neoclassical façade. It was commissioned by an Indian merchant and later leased to a wealthy Burmese businessman, U Ba Nyunt. He turned it into the first Burmese-run department store, Myanmar Aswe (roughly translating as “Myanmar Friend”). With its prime location on the Sule Pagoda roundabout, this building should have pride of place in the area’s conservation efforts—especially with the next-door Asia Green Development Bank and Centrepoint Towers impinging on the cityscape.

The building’s historical significance is hard to overestimate. Not only was it the first Burmese department store; it also housed the office of the newly established Dagon magazine, a springboard for many famous Burmese writers. The office of one of the first Burmese film studios, the “A1 Film Company” was also here. The company closed down in 1983. (Unfortunately many of its historical documentaries, filmed in the wake of Burmese independence, perished in a fire in 1950.)

The building was taken over by the government in the 1970s, which coordinated foreign tourism here until the transfer to Naypyidaw in 2005. The building is now almost completely abandoned. It is missing many windows and some of its doors are shuttered.

There was speculation about the building’s future use, from boutique hotel to office space. You will notice emergency repairs, including new roofing and damp protection that took place following the devastating impact of Cyclone Nargis in 2008.

City Hall

Address: Mahabandoola Road

Year built: 1925–1940

Architect: U Tin, LA McClumpha and AG Bray (architects), Clark & Greig and AC Martin & Co. (contractors)

The architecture of Yangon’s City Hall tells a tale of rising nationalism in the dying decades of colonial rule. It was built over a drawn-out, fifteen-year period during which the world was changing profoundly. At first this massive complex was not intended to be constructed in its present form, with its overt Burmese features. As Sarah Rooney recounts in 30 Heritage Buildings of Yangon, initial plans for a new city hall emerged in 1913. Architect LA McClumpha won the tender. British administrators saw in his designs the promise of “the finest group of architectural buildings in Burma”. But the First World War broke out, funds froze and construction stopped.

When it resumed in 1925, Burmese nationalists started a debate in the Legislative Council. They demanded Burmese forms inspired by temple architecture from the ancient capital, Bagan. Their campaign overcame Western reluctance. Burmese architect U Tin was invited to revise the designs.

But how much leeway was U Tin given? It is easy to imagine the original design without his additions, such as the peacocks, pyatthat roofs and purple nagas (dragons) on either side of the entrance. The loggia and arcade illustrate the building’s competing visions. On the one hand, the lotus flower motif lining the fourth-floor loggia is in keeping with Buddhist heritage. On the other, the design of the three-storey arcade echoes the colonial architecture of Bombay.

The building used to be painted a cream colour. Before that it was a striking green, at least for a time. In 2011, it was repainted a shade of “luminous lilac”, as Sarah Rooney vividly describes it. A straw poll suggests the new colours are not to everyone’s taste—especially the bright purple nagas!

Finishing touches aside, this vast edifice is a product of European engineering. Clark & Greig built some parts. (The city also owes them the Central Telegraph Office.) Other parts were built by AC Martin & Co. (who were also responsible for laying the city’s asphalt roads and constructing the General Post Office). Architect AG Bray (who also designed the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company building) oversaw the process.

Today the building still houses the city authority, the Yangon City Development Committee (YCDC). Its mandate stems from colonial legislation and the 1922 Rangoon Municipal Act; however, the YCDC itself was created by the SLORC government in 1990.

The YCDC is independent from the government and raises its own revenue, but the government appoints the chairman/mayor. The current mayor, U Hla Myint, took office in 2011 and is a former brigadier general. He was previously ambassador to Brazil, Argentina and Japan. In December 2014 Yangon held its first municipal council elections, but these were marred by low turnout and a controversial “one vote per household” rule.

The YCDC plays an important role in urban conservation efforts. In the 1990s, the SLORC government allowed the razing of several heritage buildings. Following popular outcry, the YCDC drew up a Heritage List in 1996. The list, which contains 189 buildings, was the first of its kind for the city. Although the Yangon Heritage Trust (YHT) deems it incomplete, it remains an important benchmark. The YCDC and other partners (including the YHT and the Japan International Cooperation Agency, JICA) are developing new zoning and planning regulations. For more information about this, please see the chapter on urban planning on page 206.

Ayeyarwady Bank

Formerly: Rowe & Co.

Address: 416 Mahabandoola Garden Street

Year built: 1908-1910

Architect: Charles F Stevens (architect), Robinson & Mundy (contractors)

This building on Mahabandoola Garden Street was once the Rowe & Co. department store, known as the “Harrods of the East”. It stands in one of Yangon’s most touristic areas, right by City Hall. With City Hall set back from the street, the old Rowe & Co. building stands out by contrast. The building was state-of-the-art: below the three storeys was a large basement, unusual for swampy Yangon. A steel frame, electric lifts and ceiling fans were some of its prized innovations, courtesy of local contractors Robinson & Mundy. Their other commissions include the British Embassy, the former Myanma Oil and Gas Enterprise Building and the former British and Foreign Bible Society. The striking tower on the street corner is one of Yangon’s iconic landmarks.

Established in 1866, Rowe & Co. was famous for its quarterly illustrated catalogues. A big Christmas tree was put up in December, brought down to Rangoon from the pine forests near Maymyo, today’s Pyin Oo Lwin. The store was where high society came to do its shopping. Rowe & Co. branches could be found in Mandalay, Moulmein (today’s Mawlamyine) and Bassein (Pathein). After independence, it became a government building, housing the Department of Immigration and Manpower. After the government moved to Naypyidaw, it stood idle for some time before local business magnate Zaw Zaw bought it. His initial plans to turn this property into a luxury hotel got shelved. Instead, his Ayeyarwady (AYA) Bank became the main tenant of this building. Its façade was beautifully restored recently.

Myanma Post and Telecommunications

Formerly: Central Telegraph Office

Address: 125–133 Pansodan Street

Year built: 1913–1917

Architect: John Begg (architect), Clark & Greig (contractors)

This large and stately building is John Begg’s third and last contribution to Yangon’s cityscape. It stands beside the High Court, designed by James Ransome, who preceded Begg as Consulting Architect to the Government of India.

As Sarah Rooney describes in 30 Heritage Buildings of Yangon, building the Telegraph Office on waterlogged grounds was a struggle. For the foundation to carry the weight of this four-storey building, wooden piles were sunk across the swampy area. They were then filled with sand, followed by a six-centimetre layer of cement.

Today only a smaller portion of the Telegraph Office is accessible to the public on Mahabandoola Road. The rest of the building serves administrative functions. A huge antenna tower marks out the building from many parts of the city. Some of the windows are partially obscured by sunshades made of corrugated iron. In their elegant dark green they—surprisingly—don’t really jar with the façade. Book vendors, food stalls and grocers line most of the perimeter.

Burma’s many rivers and creeks added to the expense of building a reliable telegraph network. (The problem repeats itself today as newly licensed mobile operators try to build infrastructure across the country. They sometimes use water buffalos to carry telephone relays across rivers.) High masts and cables were needed to overcome these natural barriers. But this did not stop the medium’s development. By the late 1930s, there were 656 telegraph offices connected by more than 50,000 kilometres of wire. They covered the entire country, which in turn connected Burma with the world.

The fate of the medium is sealed, though. The world’s largest remaining telegraphy service, in India, closed in 2013. Meanwhile the building still has counters for sending telegrams, emails and “e-telegrams”, a Myanmar-only technology.

Myanmar is one of the least connected countries in the world in terms of mobile telephony—but it is catching up. In 2013, Norwegian company Telenor and the Qatari firm Ooredoo won the tender for a new mobile phone and internet network. In exchange, they committed to investing several billion dollars in infrastructure. This will include thousands of transmission towers, often in remote areas without regular electricity supply. Mobile phones and SIM cards, which were so rare they sold for hundreds of US dollars as late as 2012, are now as cheap as in any country—and sold everywhere in Myanmar. In Yangon the service seems to be improving, but slow data downloads remain a common complaint.

Yangon Region Court

Formerly: High Court

Address: 89-124 Pansodan Street

Year built: 1905-1911

Architect: James Ransome (architect), Bagchi & Co. (contractors)

The High Court is one of Yangon’s most iconic colonial buildings. Pictured overleaf with the Independence Monument, it is an inescapable sight as you stroll downtown (or rather, weave through the fumes and traffic).

Its architect, James Ransome (1865–1944), was John Begg’s predecessor as Consulting Architect to the Government of India. When John Begg took over the position, Ransome’s High Court was almost complete. Begg judged the construction “somewhat over-designed”. Certainly the building displays a generous dose of pomp. The impression is similar to the one conveyed by Jan Morris about the British colonial High Courts of India: she describes them as “very conscious of their own importance, and into them the architects tried to build the loftiest meanings of empire”.

The towers and loggia windows feature elaborate brick patterns. The cream-painted arches, rows of balconies and stuccowork echo Renaissance architecture. (But this building is distinctive in its use of pale burgundy bricks, manufactured locally by the construction company Bagchi & Co.)

Ransome didn’t spare any bombastic detail or British imperial cliché. On the roof of each wing, a lion faces its opposite number. The tall portico leads into a vast inner courtyard. Loggias run along both the inside and outside of the building. The engineers spared no effort either. This was one of the first buildings in Yangon to have toilet and plumbing facilities as well as electricity.

Like many other buildings throughout Rangoon, the construction had to accommodate swampy soils. Sarah Rooney explains: “The clock tower was a risky endeavour and required extensive foundations made of thitya, a hardwood that is especially durable in damp conditions.”

Prime Minister U Nu’s post-independence government maintained—and improved—the British legal system. But Ne Win’s coup in 1962 changed everything. The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court was one of several people who were immediately arrested when Ne Win’s units rolled into the city. His regime did away with the Supreme Court and replaced it with a socialist variant, the Council of People’s Justices. General Ne Win controlled the appointments.

The 2008 Constitution states that judges should be appointed on merit. In practice, the president and the speakers of both chambers submit the names to parliament for a vote. Myanmar’s Supreme Court moved to the new capital, Naypyidaw, in 2005 and this grandiose building is now a local court. It is only partly occupied.

Sofaer’s Building

Address: 62 Pansodan Street

Year built: 1906

Architect: Thomas Swales and Isaac Sofaer

Few buildings evoke old Rangoon quite like Sofaer’s Building. This imposing edifice is in a fairly decrepit state today but still—despite the years, weeds and grime—retains the grandeur of its young glory days. The four-storey structure occupies the whole width of the block between Pansodan and 37th Street; it concludes the rich stretch of colonial-era architecture on Lower Pansodan Street. Its cream yellow façade features rich ornamentations. These are deteriorating and covered in soot. Its striking dome towers over Pansodan Street. You will also notice a veranda adjoining the top-floor flat, added by a lady who has lived inside the dome for the past 40 years. It affords arresting views of Rander House across the street. While the Sofaer’s exterior could do with a high-pressure clean and a lick of paint, the extent of the building’s structural decay is even more obvious inside. The courtyard is now a light shaft and rubbish dump. The ceiling is moulding in places.

But Sofaer’s Building is as bustling as it was in its heyday 100 years ago. And it is seeing some partial renovations. On the ground floor along Merchant Road, an elegant Japanese yakitori restaurant, Gekkô, has opened its doors. It was designed by SPINE Architects. When Gekkô’s owner, Nico Elliott, paid a stately sum upfront to take possession of the venue, he discovered a 1.5 metre deep pile of sewage. This took one month and plenty of manual labour to remove. Next door is a branch of KBZ Bank, which decided to split the ground floor into two levels—a highly, let’s say, unorthodox take on heritage conservation. In fact, during renovation works, KBZ started to remove the original tiles, which were reportedly imported from Manchester. The Lokanat Galleries, which feature regular exhibitions of contemporary art, are on the first floor. The galleries opened in 1971, making them one of the most established non-profit organisations in Myanmar. Lokanat represents 21 artists today. Its motto, “Truth, Beauty, Love”, has vaguely Orwellian connotations. A makeshift teahouse occupies the hallway on the second floor. The building also hosts a basic guest house on the second and third floors, as well as a few government offices and residential units. The whole set-up on the upper floors feels pretty informal and the staircases become more and more fragile as you rise through the building.

Isaac and Meyer Sofaer were Baghdadi Jews who came to Rangoon as boys. They set up a trading business together in the late 19th century importing alcohol and specialty foods. Their building opened in 1906. Isaac Sofaer, who was also an architect, made the drawings together with Thomas Swales. By then Swales had already left quite an imprint on Rangoon despite only being in his early thirties. He designed today’s British Embassy, the extensions to the former St Paul’s English School in Botataung and the former Fytche Square Building.

The opening ceremony of Sofaer’s Building was a major event that year. The Governor-General of Burma presided over the proceedings and inaugurated the building by opening its doors with a set of golden keys. Sofaer’s Building instantly became one of the city’s most prestigious commercial addresses. Tenants included the news agency Reuters, Bank of Burma and China Mutual Life Insurance Company. There were also fine liquor and commodity purveyors. The building featured one of the first electric lifts—only the shaft, cluttered with debris, remains today. The original floor tiles remain throughout the building. (They look their best inside Gekkô, where they’ve received a good scrub.) The steel beams were manufactured in Scotland. Like in nearby Balthazar’s Building, the beams were erected and supplied by engineers Howarth Erskine. No definite plans exist for the future of Sofaer’s Building—its fate is complicated by the fact that several parties own it, as is the case for other buildings around the city. More commercial redevelopments are under way on the ground floor. A full renovation, sooner rather than later, is what this magnificent building deserves.

Internal Revenue Department

Formerly: Rander House

Address: 55–61 Pansodan Street

Year built: 1932

Architect: Unknown

With its Art Deco touches, Rander House is clearly from a later architectural era than Sofaer’s Building across the road. It also feels more compact due to its height (five storeys), massing and more regular window grid. Remnants of a large portico are visible between the ground floor and the second floor, which was demolished after 1988 when SLORC decided to widen Pansodan Street. In fact, this happened to all buildings with porticos along this stretch of the road. SLORC also cut down a row of tall trees that used to line this street. (For more details on the changes post-1988, click here.)

Rander House was commissioned by traders who migrated to Burma from Rander, a city close to Surat in the Indian state of Gujarat. As Indian Muslims flocked to Rangoon in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, they coalesced into associations according to their towns of origin. One of these, for example, was the Rander Sunni Bohras Soorti Mohamedan Association. The Soorti-Rander community also maintained a Randeria High School on Mogul Street, which admitted non-Muslims as well. The Surti Sunni Jamah Mosque was this group’s main house of worship.

It is believed that by the 1930s, the owners of Rander House took over the adjacent Sofaer’s Building. (Sofaer’s is sometimes referred to as Randeria House.) Rander House itself became home to the Pakistani Embassy in Rangoon after India’s partition and Burmese independence.

This building also housed the Rangoon branch of Dawson’s Bank. Economist Sean Turnell explained to the authors of this book that Dawson’s was “an extraordinarily successful agricultural bank whose methodologies preceded many of those employed by microfinance today”. There were plans to return Dawson’s Bank to its glory days after the Second World War; however, the U Nu regime’s Land Nationalisation Act of 1954 put the model out of business. The bank shrunk to become a “high-end pawn-broking business,” in Turnell’s words. It closed down after the 1962 coup.

The British Council had their Yangon office in the building from 1947 until it withdrew from the country in 1966. (It returned in 1978 as the “Cultural Section of the British Embassy”.) Later, the Internal Revenue Department took over the lower floors. Some of the top floors became apartments for senior departmental staff.

Myanma Economic Bank Branch 1

Formerly: Cox & Co.

Address: 43/45 Pansodan Street

Year built: 1921

Architect: Unknown

The building was originally Cox & Co.’s Burma headquarters. Cox was a tradition-rich company with roots stretching back to the 18th century. It offered banking services to British military personnel. Business boomed during the First World War. Its Charing Cross branch in London had to stay open 24 hours a day to cash cheques for officers returning from the front. The company then opened offices in regions where British or colonial troops were stationed. The Rangoon branch opened in 1921. But Cox’s wartime profits were hard to maintain in peacetime: by 1923, the company was forced to scale back its operations abroad and sell its “Eastern” branches to Lloyd’s Bank. Lloyd’s itself was a latecomer to the colonial business, and the acquisition of Cox & Co. represented its first foray into the region.

Lloyd’s not only took over the banking side of Cox & Co.’s business, but also its travel and shipping agency. This may explain why this building is sometimes still called the “Bibby Line Building”. Since 1889, the Bibby Line Company ran a regular steamboat service between Liverpool and Rangoon. It took about one month and cost GBP 50 at the time (about 5,000 in today’s money). By the 1920s, several boats were making the profitable journey and several agents sold tickets in Rangoon, including Cox & Co. (and later Lloyd’s) and Thomas Cook & Sons, who had their offices on Merchant Road. Despite a sharp fall in the Burma trade following independence, the Bibby Line service continued well into the 1950s. By then, competition from aeroplanes was already stiff. The British Overseas Airways Corporation (one of the two forerunners to modern-day British Airways) was serving Rangoon from London and other destinations within the former Empire.

Today, the building’s new lick of baby blue and white paint gives it away as one of Myanma Economic Bank’s downtown branches. Most branches received a similar facelift in the last couple of years. The windows on the ground floor are covered with wrought-iron bars bearing the initials MEB. The three-storey building is stately but appears less commanding compared to the later and taller additions surrounding it on Pansodan Street. The only non-colonial building in the vicinity is just to the MEB’s right—the Myanma Economic Savings Bank Branch 1.

Inland Waterways Department

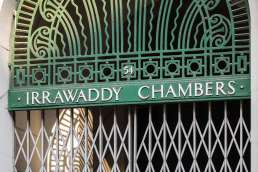

Formerly: Irrawaddy Flotilla Company

Address: 50 Pansodan Street

Year built: 1933

Architect: AG Bray (architect), Arthur Flavell & Co. (contractors)

This building stands out from its neighbours due to its recessed façade and twin Doric colonnade. Above the columns are golden clam shells, reflecting the building’s maritime connection. All doors and windows on the ground floor are set back too, to protect it from the sun. Like many buildings on the east side of lower Pansodan Street, an enormous entrance canopy stretches across the sidewalk and some of the street. It is suspended by gold-painted rods. Iron elements on windows and balconies are painted petrol green. Long-time Yangon resident Harry Hpone Thant told us:

“The pavement in front of the building used to be covered with big black slate tiles. They were slippery when wet, and caused trouble for female office workers when the rain and driving winds made them hold onto their flapping htameins (dresses), the umbrella, their sling bags and their lunch basket all at the same time.”

The Inland Water Transport Board building was built for the corporate headquarters of the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company (IFC). The firm’s founders, the Henderson brothers from Fife in Scotland, were experienced shippers. They grew their business servicing the “emigrant trade” between Britain and Canada, the United States and New Zealand. On the return journeys from New Zealand, Henderson ships would call at Rangoon, taking on shipments of rice and teak. Before long, they realised the potential of Burma’s growing economy and purchased several steamers to profit from the river trade in the 1860s. On the eve of the Second World War, the IFC commanded a fleet of several hundred vessels travelling the country’s waterways north to south and vice versa, transporting cargo and passengers. Almost the entire fleet was deliberately destroyed ahead of the Japanese invasion in 1942 to prevent the ships from falling into enemy hands.

The Ayeyarwady (today’s name for the former Irrawaddy River) flows from the country’s north to south. It is navigable all year. Other rivers include the Chindwin (a tributary of the Ayeyarwady) and the Thanlwin. The country also possesses a dense network of canals which, depending on the season, are also navigable. The British connected Rangoon more directly to the Ayeyarwady in the late 19th century by digging the 35-kilometre-long Twante Canal. This infrastructure facilitated the exploitation of Burma’s natural resources and fuelled the colonial project. By 1910 practically all teak and three quarters of rice were shipped by boat. The IFC and the Bombay–Burmah Trading Corporation (both Scottish companies) were instrumental to Britain’s northward push. This led to the annexation of Upper Burma in 1885, when the BBTC provided a casus belli with King Thibaw over a tax dispute. The IFC readily put its many ships at the disposal of the 20,000 British Indian troops. These took Mandalay with little resistance. Today, almost half of the nation’s transported goods still travel on the back of river steamers, some of them several decades old.

Myanma Agricultural Development Bank

Formerly: National Bank of India

Address: 26–42 Pansodan Street

Year built: Circa 1930

Architect: Thomas Oliphant Foster & Basil Ward

The National Bank of India (NBI) was one of the main exchange banks of the British Empire. Its Rangoon branch was set up in 1885 and a stately headquarters was erected on Pansodan Street by 1896.

In the 1920s, business was booming in this part of the world. The company decided to rebuild its branch from scratch—this time bigger, more opulent—and decidedly more modern.

The new building was finished around 1930, designed by Thomas Oliphant Foster and Basil Ward. We cover Foster’s legacy in the Myanma Port Authority section. But a few words about Ward are warranted here because his name is practically forgotten in connection with Yangon. Foster was the more experienced member of the short-lived duo but Ward (1902–1976) contributed the flair of a young architect fresh out of school. He leant towards the modern architectural language of continental Europe. A native New Zealander, he studied in Wellington and moved to London upon graduation in 1924. He failed to enrol at the prestigious Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) and, after a while, moved to Yangon with his wife. Here Foster and Ward worked on a variety of buildings that are usually exclusively credited to Foster. Apart from the NBI building, these projects include the Myanma Port Authority as well as several buildings for Yangon University. Ward returned to London in 1930, setting up a partnership with his friend from home, noted modernist architect Amyas Connell. They teamed up with London-born Colin Lucas in the mid-1930s to form a short-lived but highly influential partnership. They were among the foremost proponents of pre-war International Style architecture in Britain and designed residential projects in and around London, several of which still stand today. Along with Raglan Squire (see the Technical High School and University of Medicine-1), Basil Ward is one of a small group of architects who used their stints in Rangoon to further their international careers.

The National Bank of India building is often known as the Grindlays Bank. What follows is a tale of mergers and acquisitions in high finance, as played out on Pansodan Street in downtown Yangon: Grindlays only entered Burma after it acquired Thomas Cook & Sons in 1942. (Back then, the travel agent also had banking operations—remember travellers’ cheques?) Besides Thomas Cook’s Rangoon branch on Merchant Road, Grindlays also acquired buildings in major cities in China, India as well as Hong Kong, Ceylon and Singapore. As the Japanese army had occupied Rangoon, Grindlays had to wait almost four years before it could formally requisition its branch there a few months after the war. Grindlays’ owners, National Provincial (later merged into today’s NatWest), sold Grindlays to NBI in 1948. Ten years later NBI and Grindlays merged into the new National Overseas & Grindlays Bank. This building was their office. The name change reflected many companies’ desire to rid themselves of references to the former Empire. This was, to put it politely, out of fashion in the post-colonial age. After all NBI was no Indian bank and “National and Grindlays”, as it became known, sounded more forward-looking. In Yangon popular parlance however, the bank became known simply as “Grindlays Bank”. (This revelation concluded the rather arduous task of locating this building for this book’s research.)

In 1961 National and Grindlays Bank bought Lloyd’s Bank, which had a branch just across Pansodan Street, today’s Myanmar Economic Bank Branch 1. Eventually, as with all banks in socialist Burma, National and Grindlays underwent its last and final merger, this time a forced one: in 1963 it was nationalised and became the “People’s Bank No. 11”.

From 1970 to 1996, this building housed the National Museum. Its prized exhibit, the Lion Throne of King Thibaw (the last monarch of Burma) stood centre stage beneath a beautiful rotunda with a domed ceiling. Only in 1996 did the entire museum move into its dedicated premises on Pyay Road (now the National Museum). Today parts of the building are occupied by the Myanma Agricultural Development Bank, one of the country’s state-owned banks. Perhaps one day, this proud bank building will belong to one of the many offshoots that once owned Grindlays, the National Bank of India or the merged National and Grindlays. Among them are global players such as NatWest, Citibank, Lloyd’s and Standard Chartered. In 2000, the latter acquired the bank from none other than the Australia and New Zealand Banking Group (ANZ). It was the only Western bank to receive a coveted licence from Myanmar authorities in 2014.

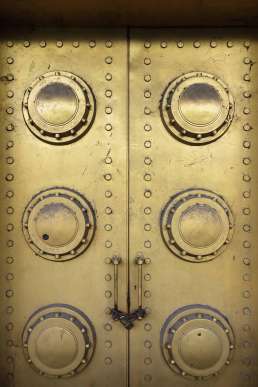

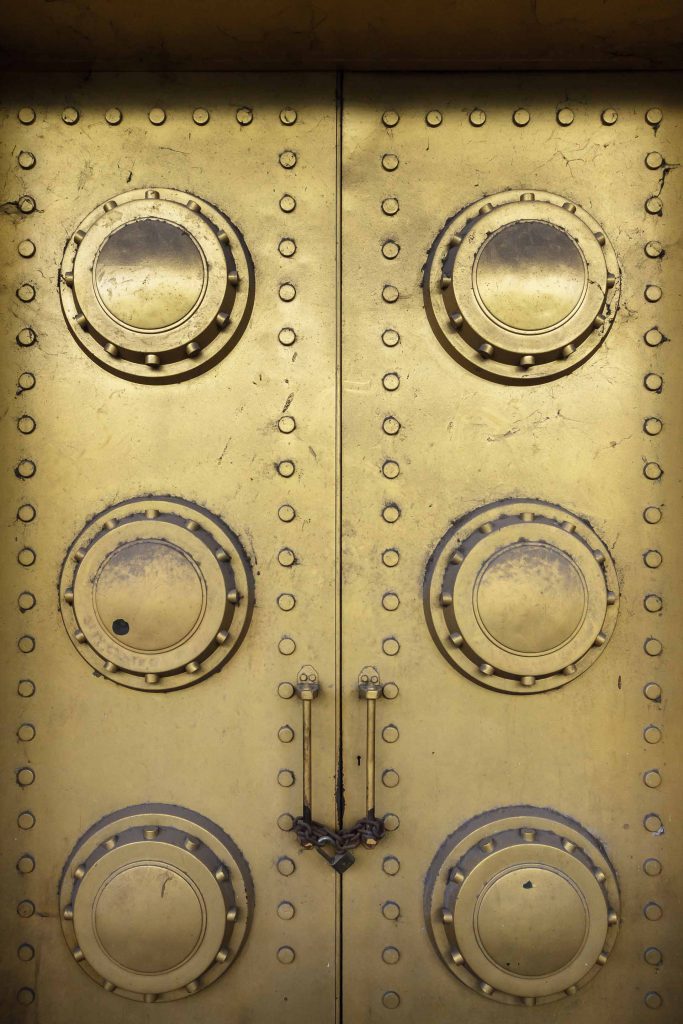

This imposing building, with its strictly geometric façade, is another reason why this stretch of Pansodan Street should be one of Yangon’s most treasured and protected thoroughfares. The columns don’t follow classical rules: they connect without any capitals. The underside of the protruding roofs is decorated with scales. Lion-headed waterspouts decorate the roofline. The small windows are set back from the columns. They are surrounded by an arched geometric pattern. The large semi-circular entrance canopy cantilevers over the sidewalk and extends onto the street, like most other roofs on this side of Pansodan Street. Remarkably, it also features a mirrored underside. The golden entrance door is worth admiring too. But at the time of writing, entry was not permitted.