Zaw Lin Myat

Zaw Lin Myat

Graduate Student of Architecture and Historical Preservation, Columbia University

Mahabandoola Garden, formerly Fytche Garden

The Mahabandoola Garden has been my favourite spot downtown ever since I was a child. The Independence Monument, fountains and greenery, surrounded by the majestic High Court and City Hall, create a true urban oasis in downtown Yangon. Especially in the hot summer, the park is a nice place to hang out in the evening as a breeze from the river cools down the day. In the 1990s, there were merry-go-rounds and Ferris wheels for children to enjoy. I vividly remember those times when I ran around the park and rode these attractions each week. Unfortunately, they have been replaced with not-so-attractive public bathrooms.

Ministers’ Building (Secretariat)

The former Secretariat is shrouded in mystery for a Millennial like me. Majestic as it may seem from the sidewalk, the Secretariat is off-limits for the general public other than you-know-whos doing you-know-what behind the layers of security, fences and thick vegetation. Until recently, I have only vicariously experienced it through the historical accounts of General Aung San’s assassination, and the independence ceremony shortly thereafter, when the Union Jack was retired and the six-star Union of Burma flag was raised. The building holds so much historical and architectural importance for British Burma as well as independent Burma. When you know its history, it can overwhelm you as you pass by on the crumbling sidewalk.

Karaweik Palace

A big boat in the form of two mythical birds can be attractive to any child. Famous ice cream on the boat added to the excitement of the place when I was little. A royal barge, it is in fact a concrete structure anchored firmly on the bank of Kandawgyi Lake. Perhaps it’s a Burmese counterpart to Venturi’s postmodern duck—except it is more elaborate in the form of a mythical bird, painted gold. Very Burmese. It makes a statement on the lake, and it is lovely to enjoy the scenery from its platform, facing the venerable Shwedagon Pagoda as if you were royalty on a pilgrimage.

Chinese Shophouses in Latha Township

Architecturally unique from all other parts of downtown Yangon, these two- to four-storey shophouses are home to the Chinese community which make up Yangon’s Chinatown. The wooden louvre windows, dougong brackets, some quite detailed, recall the Chinese heritage you find throughout Southeast Asia. These buildings might not be as grand as many colonial buildings but they make the fabric of vibrant Chinatown. Although they are largely intact on the lower block of Latha Street, they can be spotted throughout Latha Township and are always great to look up at as you navigate its bustling streets.

Warehouses at the end of Sule Pagoda Road

These long, windowless brick structures span along the Yangon River and stand imposingly at the end of Sule Pagoda Road. The architecture is clearly utilitarian. The warm-orange brick walls that make up these warehouses, arranged in a uniform and orderly fashion, have become iconic of Yangon’s port. When you walk along Merchant Road and look towards the river from the numbered streets, their presence is hard to ignore and can be appreciated in the light of the setting sun.

Sarah Rooney

Sarah Rooney

Author of 30 Heritage Buildings of Yangon: Inside the City that Captured Time

The Secretariat

It’s impossible not to include this sprawling ruin on a list of favourite Yangon buildings; it is the centrifugal point for much of the country’s modern history and looks as if it was materialised not from bricks and mortar, but from the pages of a novel by Charles Dickens. Though renovation efforts may clear away the cobwebs, the complex will always be an evocative monument to how the unforgiving decades of the 20th century shaped the contours of this former capital city.

Sofaer’s Building

You know immediately from looking at this grandiose but dilapidated building that it is somehow still being held together by the ambitions and stories of its past inhabitants. Commissioned a century ago by a Baghdadi Jewish trader, it was once an emporium of imported wonders that became the extravagant swansong of a family empire on the verge of collapse. Today, as its rooms are selectively gentrified and its sagging walls are propped up by new inhabitants, this building’s fortunes will chart the progress of a country’s hopeful, but precarious, resuscitation.

Sule Pagoda

This spiritual site pre-dates everything else in downtown Yangon. I love the way it has become integrated into the modern city, locked in place by the ceaseless whirl of traffic, the pocket-sized shops that surround it, and the barefoot flow of monks and worshippers depositing their prayers. Spend a morning or an afternoon within its shaded enclaves and you get the sense that all of life must, at some point in time, circumambulate this gilded miniature mountain around which Yangon’s urban landscape came into being.

Former Myanmar Railways Company

Once the headquarters of the Burma Railways Company, which laid the tracks that stitched together the disparate parts of the British colony, this building has been derelict for as long as I have been visiting Yangon. Under the SPDC regime, its U-shaped floor plan made it ideal for hiding a battalion of riot police that remained on standby should any disturbances threaten the enforced peace. The building has a tenacious and utilitarian beauty; as the much-publicised centrepiece of Yangon’s most high-profile property development, it will surely become emblematic of this new and unfolding chapter in the country’s history.

Surti Sunni Jamah Mosque

This splendid, wedding-cake structure seems impervious to the tremendous changes that are taking place around it. Yangon’s oldest mosque is situated on what used to be Moghul Street, which was the setting of an informal pavement stock exchange during the economically parched Socialist era where people came to trade in illicit gems, gossip, and covert land or air routes out of the country. Walk along a line drawn any which way between these five buildings, lingering especially in the grid of streets around this mosque, and you will map a route that takes you straight through the shifting sediment of the city’s historical core.

Daw Moe Moe Lwin

Daw Moe Moe Lwin

Director and Vice-Chair, Yangon Heritage Trust; Vice President, Association of Myanmar Architects

Shwedagon Pagoda

My favourite structure, first and foremost, is the great Shwedagon Pagoda. I think it gives us spiritual strength and a unique sense of security and being in Yangon. It is common for Myanmar people to tell you that their ultimate goal is “to visit the Shwedagon at least once before they die”. The stupa itself is a remarkable architectural achievement that was built in various stages through different reigns in history. There are also various fine architectural specimens on the main and lower platforms, including pavilions, smaller stupas, monasteries and image houses. Similarly, these were built across the centuries. The Shwedagon, as one of the larger public spaces in Yangon, has also long been associated with political and social upheavals in Myanmar’s history, including the struggle for independence and more recent movements. The plaques recording donations over time would make for fascinating historical or anthropological research.

Sule Pagoda and surroundings

This historic site has been the centre of the former capital since the mid-19th century. As a result of colonial-era urban planning and design, it is at the heart of the city and has been the most popular site for public gatherings ever since. It is surrounded by a rich architectural landscape of domes, towers, minarets, spirals, and lush green trees with seasonal coloured blossoms. This is quintessentially Yangon.

Yegyaw High School

An early 20th-century teak structure has served as the local high school in a south eastern corner of the city since the day it was built. The Methodist Burma Mission established it, after purchasing the plot in 1906 to build a boys’ school. The mission completed a church, two high schools and a missionary house in the same block of Upper Bo Myat Tun Street (formerly known as Creek Street). Although it was originally a missionary boys’ school, it also served as a gathering space and shelter for the local community, and became a springboard for social and political organisations. It currently serves over 2,000 high school students. It also features an indoor court for sports activities such as badminton or the more traditional chin-lone, Myanmar’s traditional sport, where players keep a small woven rattan ball in the air by passing it to one another with agile, dance-like footwork.

Scott Market (Bogyoke Market)

An abiding image of the market I’ve always had since my childhood is of an old man with a big hard hat dozing off on the street. The market is a single-storey building with a main aisle, flanked by three wings at each side. There are double-storeyed shops lining the perimeter. The market has always been a gathering place, for traders; tourists and the trendy; for youngsters and creatives to hang out; for ladies of all walks of life to show off their fashion sensibilities; where new styles and ideas are introduced.

Central Fire Station

This fine Edwardian building is a prominent piece of architecture on Sule Pagoda Road. It has always complemented the sight of the Sule Pagoda. The road leading towards the stupa, together with the fire station on its right, has been a showcase of Yangon’s unique street scenes for decades. It was built in 1913, when Rangoon’s municipal government saw the need for the emergency service in a fire-prone city. The Department of Fire Fighting deserves credit for maintaining the building in good condition despite its old age.

U Hpone "Harry" Thant

U Hpone "Harry" Thant

Senior Advisor, Myanmar Tourism Federation

Old Police Court Building (New Law Courts Building)

The engraving on the façade says the Governor of Burma erected the building in 1931, in time for Queen Victoria’s Jubilee. Since then it has lived through some of the most interesting periods of Myanmar’s history. It became the headquarters of the dreaded Japanese secret police, the Kempeitai, during the Second World War. After the war it was the main police court building in Yangon. It was also used as offices by the socialist regime after 1962.

But this isn’t just a lifeless concrete structure. The old building shared in the joys and sorrows of the people under its roof. The walls would reverberate with laughter and songs during the Myanmar New Year staff parties every April. It cried in silence when a young female employee drowned in the Yangon River in a ferry mishap, right under its nose. And there was the mysterious case of the old rusty iron safe on the veranda: nobody knew when or who put it there, or why, let alone what was inside. Another time, a night duty officer saw a snake on his rounds and when he captured it, found it was a female cobra with eggs in her belly. Oh my God!

Lim Chin Tsong Palace

It is an imposing structure with spires constructed in Chinese style. There were rumours of a tunnel under the main building to connect it to another similar, but smaller, structure on the other bank of Inya Lake. Some say there was a secret basement. There was also talk among envious locals who claimed Chin Tsong was so rich that he burned banknotes to boil his tea kettle. Although not in Myanmar architectural style, it shows the cultural diversity of the city.

Boat Club and Kandawgyi Lake

The Boat Club was strictly the domain of the “whites”. No local Myanmar members were accepted; they were even forbidden from entering the building. After independence in 1948, the lake reverted from “Royal Lake” to its Myanmar name of Kandawgyi, which means “Great Lake”. The Boat Club was renamed the Pyidaungsu Club (“Union Club”) and the doors of the clubhouse were opened to local people (if they were elite or powerful).

The lake’s origins are shrouded in mystery. Legend says it was formed when King Okkalapa used the earth from this place to make bricks for the great Shwedagon Pagoda. Others suggest the lake was formed when the Head Minister of Dagon (Yangon’s historical name) dammed a small creek draining into the Pazundaung River to water his war elephants. But however the lake actually emerged, it has become Yangon residents’ favourite spot for rest and relaxation.

Rangoon Turf Club

Sundays were race days: Rangoon’s high society would gather at the Rangoon Turf Club in all their fineries, sitting in the Members’ Stand on the western side of the grounds. The lower classes had to enter by the eastern gates. General Ne Win, who took over the country in 1962, was a regular visitor at these Sunday meets even before he took power. Later he decided to abolish horse racing. But the former Members’ Stand found a new life. They became a stage for delegates from the country’s 14 States and Divisions to give glowing speeches and extol the virtues of socialism. Today the grounds are overgrown with weeds and tall grasses but the ancient crumbling walls of the Members’ Stand might still be remembering the voices cheering the winning jockeys—or are they cheering the glories of socialism? Who knows what they might tell us if they could speak!

Ministry of Hotels and Tourism

First built by Indian investors, the building was partly destroyed during the Second World War—suffering extensive damage to its façade in particular. After the war the Ministry of Commerce had some of its offices here. After 1962, the Revolutionary Government substituted the Ministry of Commerce with the Ministry of Trade and created state-led corporations to boost the economy, notably in the tourism sector. Tourist Burma had its offices here. Although it was the sole authorised tourism agency, it never really looked busy. The counters were silent and covered with faded and frayed pamphlets.

Fortunes changed when the building became the Ministry of Hotels & Tourism (MOHT) in the early 1990s: the halls were filled with eager entrepreneurs hoping to attract international visitors to the world-famous Golden Land. Investors were lining up to build new hotels and resorts, new airlines and cruise ships, hoping for a boom in tourist arrivals. When the whole government machinery moved to Naypyidaw, the MOHT of course followed. Now, sadly, the once majestic building stands forlorn and forgotten in the shadow of the Sule Pagoda.

U Sun Oo

U Sun Oo

Principal Architect, Design 2000; Board Member, Yangon Heritage Trust

City Hall

The City Hall displays a successful expression of Myanmar national character in a civic building design. It features a good composition of Myanmar traditional roof forms and decorative elements, for what was a novel type of building at the time.

Architect U Tin designed the City Hall. After its completion, he received the title of “Sithu” (similar to a British knighthood) from the government. He only designed parts of the building; for the rest, he inherited a British colonial design, but was able to nicely articulate the two. It has become an iconic building of Yangon.

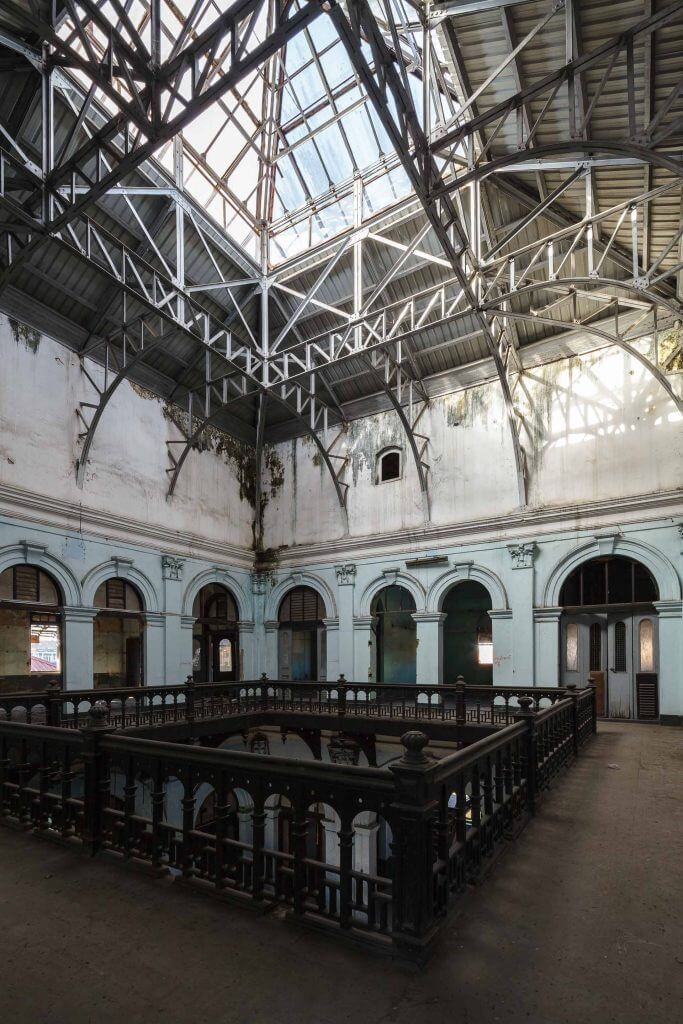

Secretariat

This was a totally new design, brought in by the British at the end of the 19th century. What was an “alien-like” structure at the time became popular and gradually accepted by a majority of Burmese people over time. After a few decades, the building also became part of Burmese architecture’s history. Now it is one of the best-loved buildings in Yangon, and acknowledged as one of the country’s cultural assets. Religious and civic building designs of later periods in Burma were influenced by this good example of colonial architecture.

Buddhist Museum and Library (Pitaka Taik)

This building is a successful, modern expression of Buddhist religious architecture in a new Buddhist library building design. A foreign architect designed it. You can see how the architect improvised, or modified forms and decorations from traditional religious buildings. And yet this isn’t a re-interpretation, but a strongly traditional building.

Thakin Kodaw Hmaing Mausoleum

This is one of the best examples of progressive architecture design in the history of Myanmar architecture. It features simplified and modified traditional Myanmar design motifs. The basic form is pure and geometric. The daring use of deep red and gold in the interior resembles the traditional colour combination of Myanmar palaces.

YMCA building

This is a good example of second-wave modern architecture in Burma, exhibiting a style that was popular in the late 1960s and 1970s. It flourished in the socialist period and the style can be seen in a lot of Yangon’s residences and in some large towns throughout Myanmar, thanks to the efforts of leading architects of the style, such as U Kyaw Min and Captain Kyu Kyaw.